A Ukrainian Easter in the High Tatras

...with a side-order of wax-resist and an egg-dumpling

Many years ago in the Olden Days (my kind of time), when Eastern Europe was still under communism, while travelling in Eastern Europe for reasons of filming a tv series, I found myself in Easter week in the High Tatras on the Slovak-Ukrainian border among a farming community who were celebrating Easter in the old, pre-communist way.

My hosts were Ruthenes - Ukrainians from the western part of the country - marooned on the wrong side of the border in the aftermath of WW2. The community had managed to avoid collectivisation by reasons of stubborness: an unwillingness to give up language (regional), regious beliefs (Western Orthodox Christianity) and a self-sufficient way of life. But mostly owing to the presence of undocumented wolves and bears in the surrounding forests.

The year was 1992, the Iron Curtain was just beginning to lift, and there was a new and optimistic enthusiasm for the most important celebration of the Orthodox year. And since the Ruthenes of Ludomirova, my hosts, had managed to keep to the old ways, there were visitors from Kiev - sociologists and historians - anxious to learn what had been lost and might be restored once the Russians went home. Meanwhile, the younger members of the family - parents and children - had returned from work in Bratislava to help their grandparents in the fields planting potatoes, a perishable crop of no interest to the apparatchicks since it was subject, given half a chance, to sprouting.

At the farmstead, spring was well-and-truly sprung, the chickens were back in lay, providing plenty of eggs to break the Lenten fast, and there was milk and cream for the buttermaking as the cow had just delivered her calf. The season in northern Europe is late - the earth warms up ready for planting no earlier than Easter, which is the time when young animals are born.

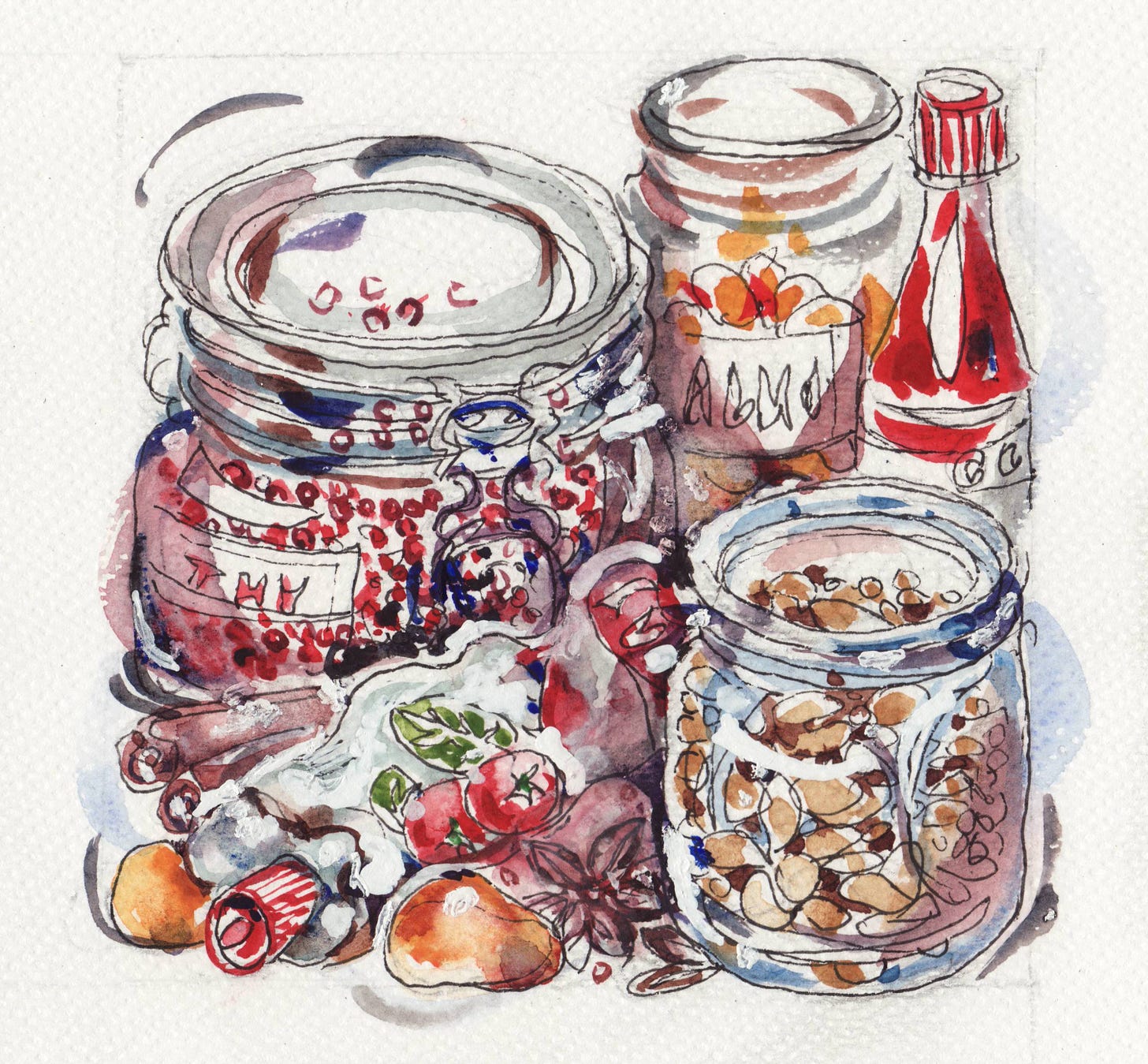

Latitude dictates that the festive East meat is not lamb, as it is in southern Europe and around the Mediterranean, but ham from the brine-pot, served with the last of winter stores - jams, pickles, jars of salted or sweetened vegetables and fruits - brought up from the cellar and displayed on the festive table for all to give thanks for safe delivery from winter and the promise of summer to come.

To accompany all these good things, the Easter babka, a buttery, egg-enriched bread prepared with a yeasted dough that must be kneaded long and hard in the bread-trough, a split, hollowed-out tree-trunk a couple of meters long, so that it’s as light and feathery as a sponge-cake. And the ham must well-soaked till the water no longer tastes salty, then cooked long and gently in a closed pot in a cooled-down oven and basted regularly, so that it’s juicy and tender and easy to carve. But the main event, an accompiment to the ham, is the egg-dumpling, a round golden ball prepared with eggs and cream scrambled together till set hard, then tipped into a pudding-cloth and set to drip into a bowl beside the fire overnight, till well-drained and firm enough for slicing.

Meanwhile, all the children had been kept busy decorating eggs to include in the Easter basket, a display of all the good things the family could provide, taken to the churchard to reassure the ancestors that all was well with their descendents and provide news of birth, marriages and departures. Once ancestral duties had been discharged, the basket was carried up the hill to the church-porch for a blessing by the priest, soberly dressed in black as befits Good Friday, with a sprinkling of well-water from a posy of new leaves.

Wax-patterned Easter Eggs

1. You’ll need multicoloured candle-ends (white, if unobtainable), a large-headed pin stuck into a cork, and the appropriate quantity of eggs for decorating. Empty out the eggs by making a pin-hole at either end and blowing until all the contents have been evacuated, saving the contents for the egg-dumpling.

2. Melt the candle ends, keeping the colours separate in saucers or metal jar-tops. Holding the egg firmly in one hand, big-end upwards, dip the pin-pen in the melted wax. Now, starting half an inch below the apex, dab on a blob of wax and drag it up towards to give a tadpole-shaped dash. Continue to dip and drag upwards to meet the thin end of the previous dash so you have a sunburst pattern.

3. Repeat with the other end of the egg - obviously you don't hold the egg by the patterned bit or the wax will melt. Fill in the gaps with more sunburst patterns round the sides. Vary the effect, if you like, by using alternate short and long strokes. Or if you have no coloured wax and only white eggs, dip the waxed egges in diluted food colouring to throw the pattern into relief.

P.S. Beloved paid subscribers will shortly be provided with recipes for the egg-dumpling (a least a dozen eggs - you have been warned) and a yeast-raised, buttery, eggy babka (no dried fruit or nuts) that’s first formed into a plait and then baked in a tall mould like a chef’s hat.

P.P.S. For the Ukrainian way with pickles and preserves, consult any or all of Olia Hercules’ wonderful books on the cooking of her native land, particularly her glorious Summer Kitchens.

P.P.P.S. For the true story of Easter in the High Tatras in 1992, download the Ruthene episode in my 13-part t.v. series, The Rich Tradition of European Peasant Cookery, at https://www.talkingoffood.com/watch/series-2/the-rich-tradition.html

I watched the Ruthene episode of your series -- delightful immersive food and cultural anthropology. I love how you are able to join in with the women, who are responsible for most food preparation, with a depth that Anthony Bourdain, Andrew Zimmern, and later Yotam Ottolenghi as male traveling/inquiring cooks never could. I look forward to watching the rest of these lovely videos. I have a treasured copy of _The Old World Kitchen_ on my bookshelves.

Lovely