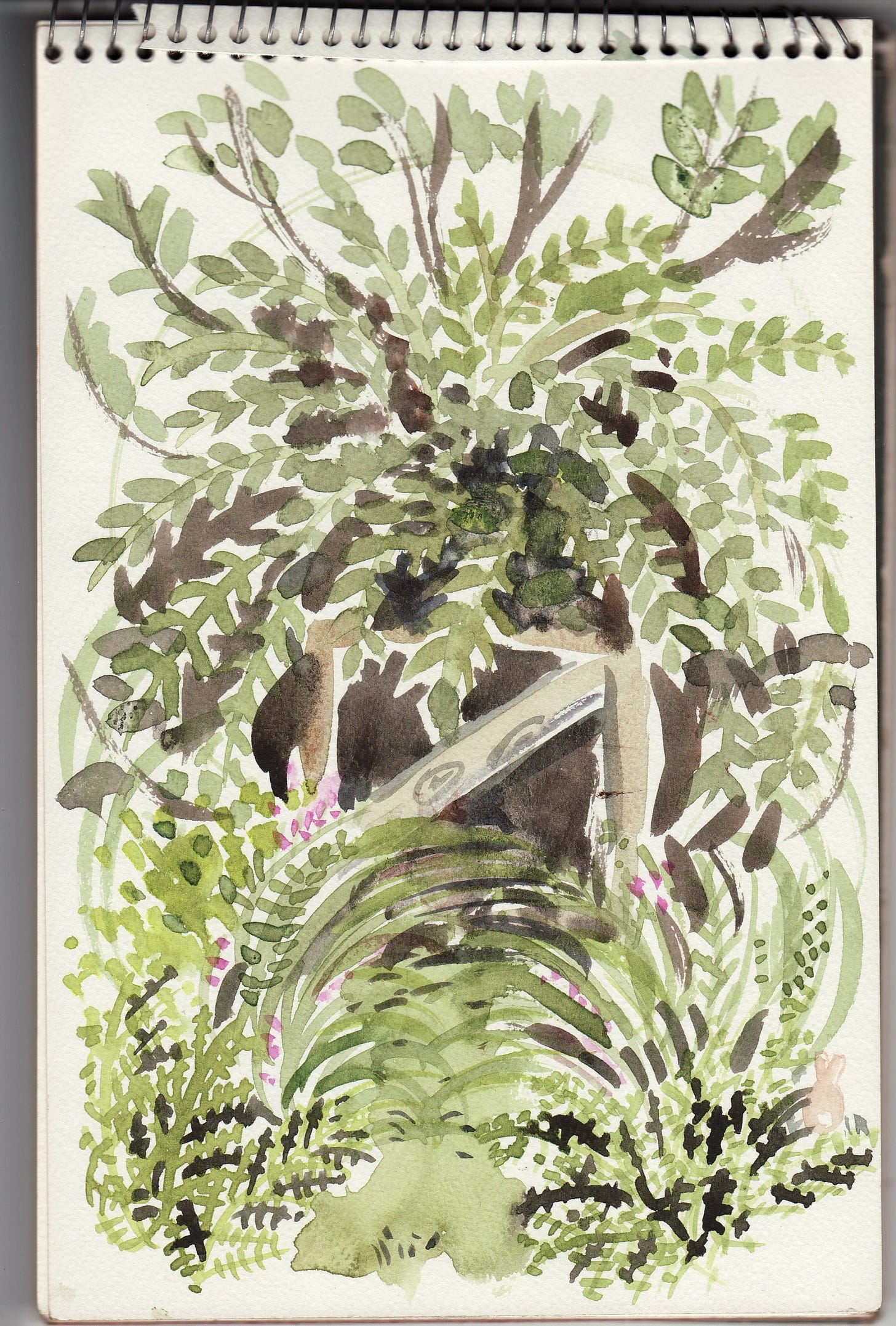

Some things are too good to overlook. Take, for instance, Japanese knotweed, Polygonum cuspidatum aka Fallopia japonica, a member of the buckweed family planted as pheasant-cover on Victorian shooting-estates. The necomer liked its adopted habit enough to spread itself exuberantly through root and seed throughout the land, particularly along railway sidings, on wasteland and in half-neglected gardens. Among the latter, the overgrown garden I once had charge of in the Hebrides, where I lived for a time in the 1990’s. Greens were hard to come by on the islands. The growing season is short, summers are often rainsodden, and the nearest shop (cabbages, mostly) was ten miles across unpaved roads from my cottage in the wilderness.

The garden, once walled but now derelict and unploughed for a century, produced nothing much but a tall stand of what looked like flowering bamboo, collapsable in winter but regenerating in spring. Identified a knotweed, according to my gardening manual, it’s a noxious weed. On the other hand, the tender young stalks picked before the seed-head forms, says Yan-Kit So in Classic Chinese, are edible and good. The stalks, like bamboo-shoots, turned out to be hollow, the flesh crisp, the juices glaucus (a texture much liked in Chinese cooking) and the flavor refreshingly spring-like - sharp and lemony. To gather for the pot, snap off the young growth at the point where the stem bends rather than breaks. Strip off any hard whiskery outer layer and tough leaves, and chop into finger-length pieces. To serve raw as a salad, drop briefly in boiling water get rid of the bitterness, drain, chop and toss with a little sesame oil, rice-vinegar, soy-sauce and slivered ginger. To prepare as a stir-fry, slice on the diagonal, toss in hot oil with garlic, chilli and ginger. Just the thing with the last of the shredded cabbage in spring.

.

Naturalised in the hop-gardens of Kent, the young growth of Humulus lupulus, a trailing vine whose pretty green flowerheads are used to preserve and flavour beer, was once sold in vast quantities as the first new greens of spring to the workers of Victorian London. When unblanched. the flavour is much like wild asparagus: sweet, chewy and a little bitter. When blanched - earthed-over to protect the tender young shoots from the light - the shoots are mild and grassy, like white asparagus.

Although the trade vanished in Britain - you’re more likely to find young shoots at the base of an ornamental golden hop - the crop is grown commercially and enjoyed as a spring shoot throughout Europe wherever beer is brewed. In Germany and Belgium, Europe’s great beer-brewing nations, they like their hop-tops blanched. In England, however, the crop was eaten green, picked when no longer than a hand’s width from the base, trimmed to no more than four leaves from the top of the stem, and, if their natural bitterness is not liked, says the great Dorothy Hartley writing in the 1930’s, soak the shoots in salted water for an hour or two, then steam till tender. Serve with melted butter; or dice for inclusion a dried-pea soup; or slice into a white sauce instead of capers to accompany a joint of Kentish marsh-mutton. In Belgium they take them with a soft-boiled egg for dipping. The Dutch like them with an hollandaise sauce (what else?) and in Italy, they’re treated as every other spring shoot - plain-cooked and dressed with olive oil, sea-salt and wine-vinegar.

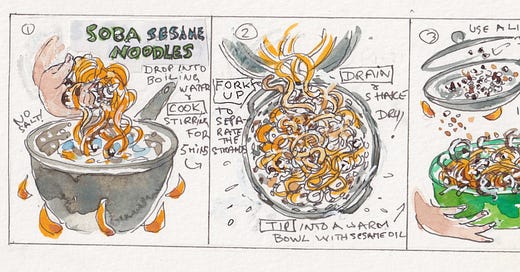

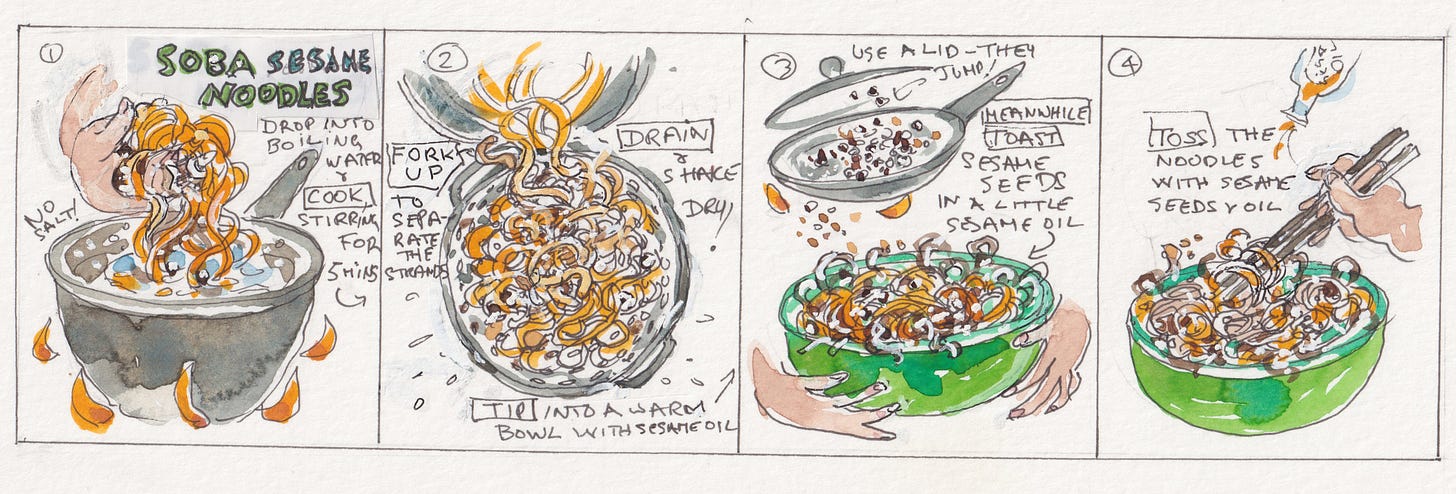

Commonest of all wild-gatherings available for free are bracken fiddleheads, the young shoots of Pteridium aquilinum, another invasive weed that’s spread itself merrily throughout the northern hemisphere and pokes its furry new-born curls on a long green stalk above last year’s growth. Most fern-varieties produce edible fiddleheads, though some are more palatable than others. All are to some extent carcinogenic if consumed in quantity, as happens in Japan, where bracken-fiddleheads are sold sous-vide in the fresh-veg section all year round. Dorothy Hartley, great chronicler of all things rural in the 1930’s, says country people gather their bracken-shoots for the pot when still tightly curled and no more than three inches high. They have a smoky flavour rather like Darjeeling tea, she says, and you either like them very much, or not at all. To prepare, cook till just tender in boiling salted water, drain thoroughly and serve with a dipping sauce of melted bacon-dripping. In La Cuisine de Plantes Sauvages, Clothilde de Boisvert recommends preserving young bracken fiddleheads, lightly cooked in water, under salt in a jar. Japanese cooks serve them as a salad with a dressing of sesame-oil, rice-vinegar and soy-sauce. In China, they’re steamed and tossed with oyster sauce, or combined with noodles in a broth.

P.S. Beloved paid subscribers will shortly be in receipt of an all-purpose recipe for Singapore Fried Noodles that includes any or all of the above. Nothing to it, really.

P.P.S. For more on the garden in the Hebrides, check out the Mull episode on my 13-part series, The Rich Tradition of European Peasant Cookery, at https://www.talkingoffood.com/watch/series-2/the-rich-tradition.html

I'd always been told to cook fiddleheads to tender, rather than leaving them a bit crisp or al dente. But I learned from friends what can happen if you don't: there's something toxic in them that needs to be neutralised by cooking...if not you get a bad gut-ache etc as my friends did.

I don't know the chemistry though. Do you?