Just because it’s Carnival in Notting Gate where everyone is hot and steamy and all dressed up in feathers and not much else, doesn’t mean a person can’t cook up a pepperpot.

Every island in the Caribbean has its own particular version of the fiery all-in one-pot stew, and every household has its own variations. My own kitchen experience as a home-cook (I’ve never been a chef - can’t chop onions) lies in Europe and Latin America. However, since I’d just found employment as cookery-columnist for a long-vanished London evening newspaper, I needed to know what so many of my fellow Londoners already knew, but I did not.

In the 1980’s, while my children were still at school and we lived in south London, a short bus-ride from Brixton market, I knew very little about what everyone else in the queue was discussing with the stall-holders - the dishes that could be prepared with cassava, plantain, jackfruit, okra and breadfruit.

To my rescue in those far-off days came Anita Noakes, Jamaica-born Londoner, who learnt her cooking at her mother's knee. She had, she explained cheerfully, been in the kitchen for forty years - give or take - which suited her just fine. Now that her own children were grown and gone, she was preparing a new venture, a wine-bar serving authentically Jamaican food using authentically Jamaican ingredients to a new - hopefully sophisticated - generation who might have forgotten, or never knew, how delicious Caribbean food could be.

When Anita first arrived in London with her mother and three sisters in the 1950’s, the plaintains and yams, chowchow and scallions - ingredients her mother was used to cooking for the family - were hard to come by. As all those who need to adapt to new places, she replaced the sweetness of Caribbean raw materials with carrots, swedes, and spring onions.

By the time we met, Anita was planning the menu for her new venture, costing-out the ingredients she'd need to draw in customers willing to spend their hard-earned cash on what was available far mofe cheaply in a fast-food outlet two doors down. The ingredients her mother had found impossible to obtain in the 1950’s were no longer a problem. You could find anything you wanted in the street-markets that catered to a West Indian clientele in Brixton, Deptford and Dalston. Everything was available from flash-frozen red snapper to Scotch bonnet peppers to slabs of stiff-as-a-plank saltfish - at a price.

The same week that Anita and I met in Brixton's Saturday market to check ingredients and prices for the new venture in preparation for an article I intended for my column, feelings were running high on profiteering in Caribbean imports. Politicians with loudspeakers were out in force. Talk was of a return of the Brixton riots of ten years earlier. Marketplaces have always been places where people gather and talk. A politician who doesn’t know the price of bread is in serious trouble, particularly when the rich can afford it and everyone else can’t.

Meanwhile, Anita decided her menu should not be too outlandish. Those who don’t know much about Caribbean food can be surprised by how easily it fits into what’s already familiar, and how delicious it is. And those who do know, love it anyway, but expect it to be better and even more delicious. A good cook will always make something, however familiar, taste better and more delicious - which is the reason chefs get paid for what they do, and home-cooks don’t.

Take for instance, Anita’s mother’s Chicken Fricassée, which is cooked with plenty of rich juice so there’s enough to sauce the traditional rice-and-peas that come with the dish. Ore a crab-patty, a fistful to eat on the run. Or Anita’s special akee salt-fish - rock-hard fish-flesh soaked till soft but still a little chewy, then cooked with tomato, peppers and onion and eaten with akee, a golden yellow stone-fruit, a close relative to the Chinese lychee, that’s poisonous when unripe - one good reason to buy it ready-cooked in a can.

Then there are all the side-dishes, the plain-cooked starch-foods that fill you up when you’re tired and hungry: fried plaintain, slices of boiled yam, or roasted breadfruit baked in the oven - and, for a treat in season, young okra pods, sweet and delicate as asparagus-spears, cooked briefly and plainly in boiling salted water.

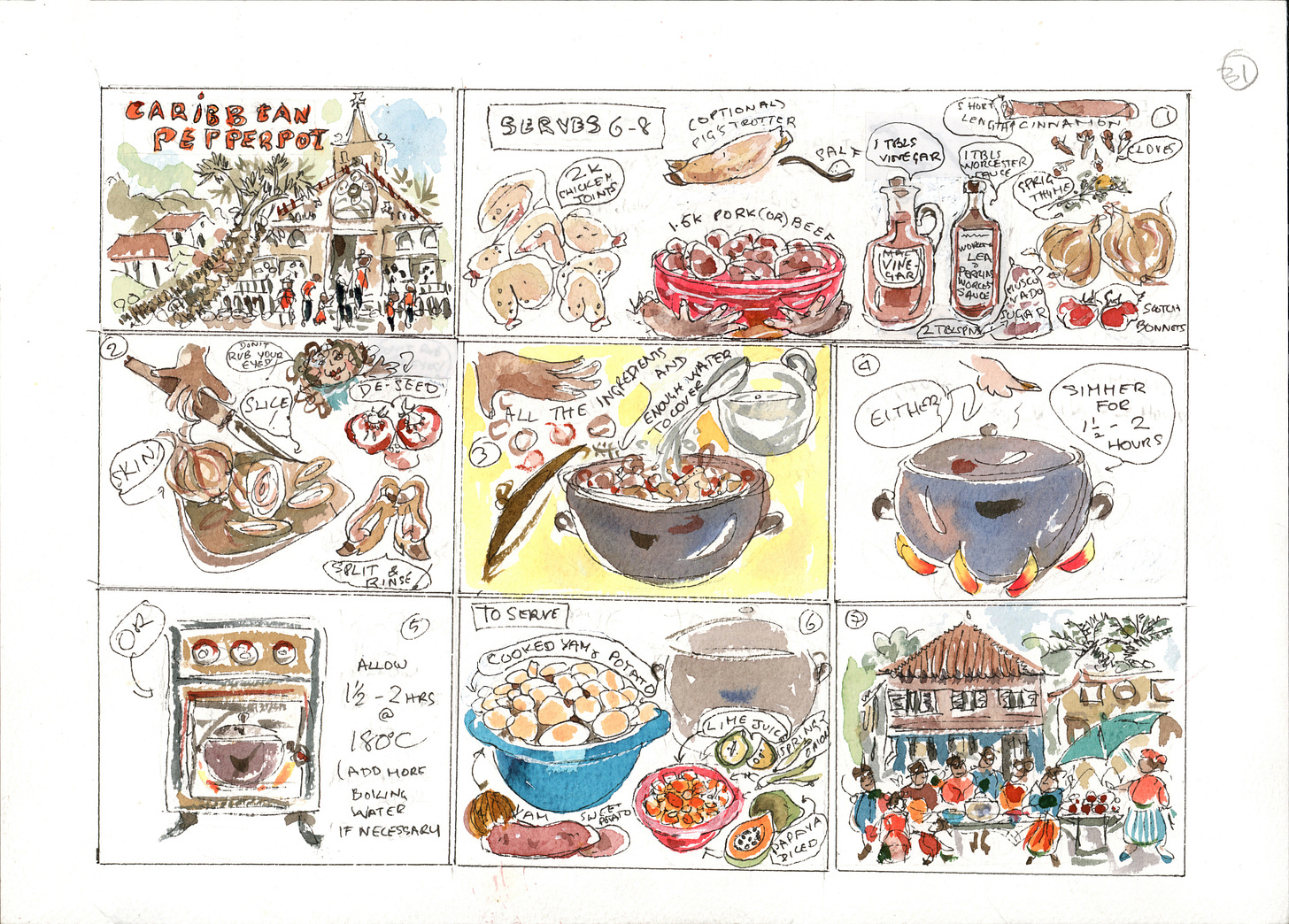

And there must, of course, be a Sunday special. Something good to enjoy at leasure - perhaps ordered in advance to take home and share with the family - what else but an authentic, non-negotiable Caribbean Pepperpot.

p.s. Beloved paid-subscribers (you know who you are, and I’m happy to report that we’re fast growing in numbers!) will shortly receive recipes for Chicken Fricassée, Rice-and-Peas and an easy recipe for Jamaican crab-patties (think of a crab-stuffed Cornish pasty - why ever not? - but with coconut and spices).

p.p.s And yes, Anita did indeed open her wine-bar, and to great acclaim for many years. However, the London evening newspaper that employed me to write recipes didn’t last nearly as long.

That's such a great thing to hear L! What's the L stand for and what are you up to since then? Magnus was such a wonderful editor, lucky us! And so pleased EPC is still travelling with you. xe

Please, please, please Elisabeth, turn these writings and your sweet paintings into a book. I'm not a one for serials - I want the whole thing in my hand, turning pages, that I can read and reread at my leisure.