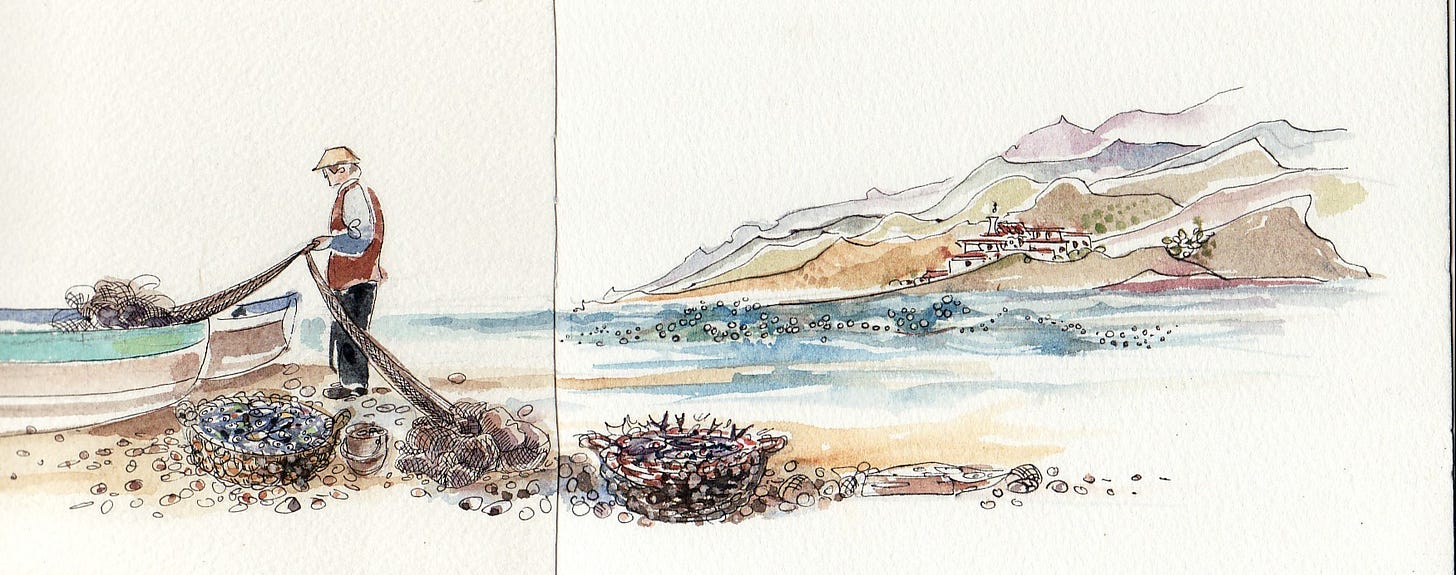

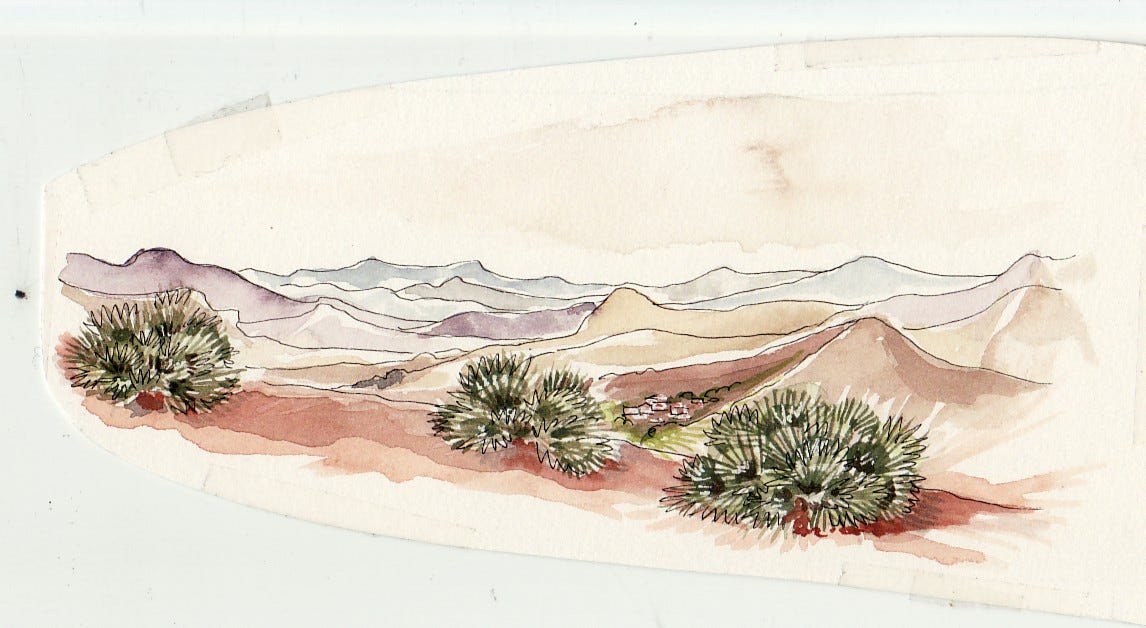

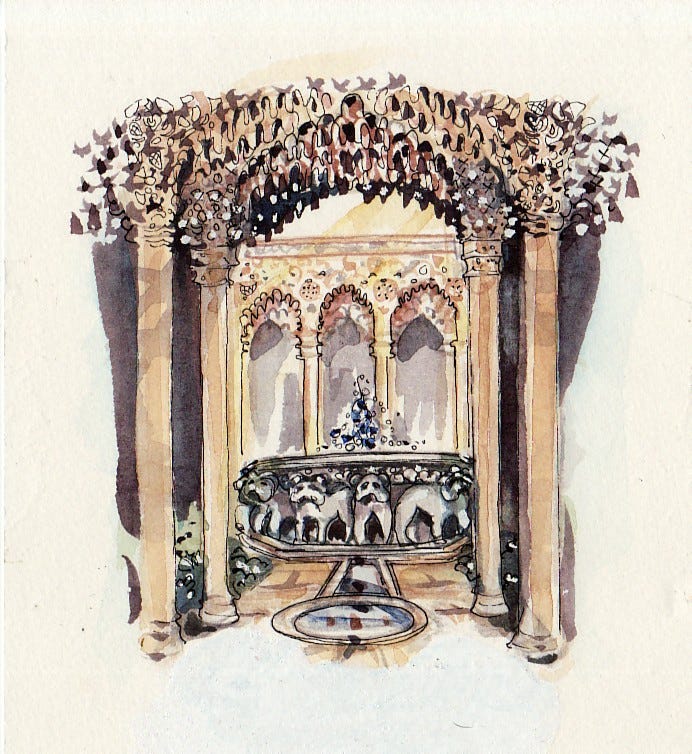

Escape the heatwaves wherever they may be and stay at home with a neat little reprint of my very own Classic Spanish Cooking (first published in 2005 - fancy that!). The new edition is illustrated with photographs rather than my watercolours, as in the original, which sent me back to my notes and sketchbooks from the days when I lived in Andalucia. I'd been bilingual in Spanish since I was six, result of a diplomatic upbringing (I was a step-child, war-orphaned, mother re-married to a British diplomat) which gave me a taste for life among the Latins, mostly in South America but also Spain - very different from dismal 1950's ration-booked Britain. Married in 1963 at just turned twenty-one, with four children born in quick succession, I decided to move my growing family to a remote valley in Andalucia, since the wilds of South America looked like a bridge too far. And no, I don't remember consulting their father (he was too busy doing important other things). Good. I'm glad we've sorted that out (plenty more in my memoirs, Family Life and My Life as a Wife). Which brings me back to culinary habits. Spanish cooking knows exactly what it is. It's not French, though Catalan and the old Languedoc language have much in common, the Basques are native to both sides of Pyranees and Galicia is more or less Celtic. It's certainly not German but does have a relationship, historically, with what used to be The Low Countries, while its ruling family inherited the Hapsburg chin. It shares much with the southern and midland Italians (the Borgia Popes were Valencianos) and there was much coming and going with the New World through the port of Seville, not so long ago a Moorish city with roots in Damascus.What we and our neighbours in the valley ate for dinner began at home for those who were more or less self-sufficient (roughly until the 1980's and the departure of the old dictator, Generalissimo Franco). What could not be grown, husbanded or gathered was bartered or paid for in the market place. By ten o'clock of a weekday morning the inhabitants of Tarifa, our local market-town, knew just what to expect of the day's rations. If the butcher had had a delivery of young beef from the Cadiz bull-ranchers, that evening the town's earthenware cazuelas would fill the air with the scent of garlic, bayleaf, cinnamon and the rough red wine of Jumilla. When the inshore fleet came in with a fine haul of sardines or purple-veiled sepia, cuttlefish, or when the migratory tuna shoals were running though the Straits on a spring tide, the breeze carried the fragrance of olive oil heating in a thousand frying-pans. The traditional cooking of Spain, then and even now, depends on the excellence of her raw materials and a culinary habit that allows good food to speak for itself. Meats are sauced with their own juices, shellfish are expected to taste of the sea, vegetables are picked and cooked with an eye to youth or maturity, and fruits are eaten in the proper season (oranges and melons in winter, grapes and peaches in summer). Everyday dishes are seasonal. For celebrations, quality counts over quantity: even the poorest households are prepared to pay for just a little of the best. My neighbours in the valley, self-sufficient and frugal, ran herds of semi-wild Iberico pigs - pata negra, black-foot, last of foraging herds of the Mediterranean - in the cork-oak forest that surrounded us as a cash-crop. Every household - mine too - kept a stye-pig of the old Iberico breed (the ubiquitous Large White didn't arrive in force until the 1980's) to provide our families with winter stores. Our neighbours, throughout our time in the valley, lived in much the same way as their ancestors did. Hardship - famine - came from war or the whim of the landlord - at least until the 1980's brought mass-tourism and jobs to the Costas, and the countryside began to look for an easier life in the cities. Closeness to the land and an understanding of what can be grown or gathered or husbanded, good food prepared as it should be in the time that it takes, remains the heart and soul of the Spanish way of life. Pan, amor, y pesetas - bread, love and money - is the traditional toast at table. The traditional reply, y tiempo para gastarlo, is a warning to take your time. Closeness to the land and what can be grown or gathered or husbanded - good food prepared in the time that it takes - remains the heart and soul of the Spanish way of life. Pan, amor, y pesetas - bread, love and money - is the traditional toast at table. The traditional reply, y tiempo para gastarlo, is a warning to take your time.Ajo blanco

The cooks of Granada, last redoubt of the Moors in Andalucia, kept the print of the caliphate in the kitchen long after the Re-conquest. Among Middle Eastern habits is an almond-milk gazpacho that never succumbed to the New World's tomato. But be warned, it has a kick like a mule, so choose mild summer garlic with no sign of sprouting.

Makes about a litre

1-2 thick slices dried-out white bread, crusts removed

100g blanched almonds, roughly chopped

2-3 fat, juicy garlic cloves, skinned and crushed

1 tablespoon olive oil

1 tablespoon white wine vinegar

1 teaspoon sugar

1/2 teaspoon salt

To serve

A few small white grapes, peeled and pipped

Drop the bread (roughly torn) into the blender with the rest of ingredients, add half a litre of cold water, and process till smooth. Dilute to a milky consistency with more cold water (about another half-litre), taste and adjust the seasoning. For extra smoothness, push through a sieve - or not, as you please.

Transfer to a jug and chill in the fridge. Pour over a single ice-cube into short tumblers and drop in a couple of peeled grapes. Serve as tapa with toasted, salted almonds and juicy green olives, or as palate-sharpener with a serious main-course salad (Granada grows artichokes and all manner of excellent vegetables).

p.s. beloved paid subscribers will shortly be in receipt of a couple of summer recipes - watch this space!

p.p.s. more Andaluz cooking with my own illustrations in a new all-singing all-dancing edition of The Flavours of Andalucia (Grub Street - bless their little cotton socks).

Delicious! Of course reminds me so much of my Tuscan/Etruscan neighbors although we were far from the sea and its riches. But so much is similar. And so very much has changed in the years since we had these life-changing experiences, no?

Wonderful! Thank you!