Couscous, the oddest and most sophisticated of the grain-preparations the wheat-growing areas of the Mediterranean littoral, came into my life when I lived in the wilds of Andalucia in the 1970’s with my young family.

At the time, passports had to be inspected and stamped every three months as proof of non-residence, much as now in the aftermath of Brexit. Memories of war - Civil as well as WW2 - were not forgotten. Brother had fought against brother, neighbour against neighbour, outsiders were likely to be informers or worse. Galician Guardia Civil were brought in to police the Andaluz (my children attended primary school in the local police-station). And under the dictatorship of General Franco that followed, foreigners were not to be trusted.

I, however - brought up in Latin America as a diplomat’s step-daughter - was well used to such situations. Passport-stamping was just one among other inconveniences that could be solved discreetly with a folded banknote tucked into a passport. Furthermore, once I’d discovered the possibilities of a diplomatic visa when travelling to meet my parents, I had no difficulty working my around officialdom (a confidence that’s never left me and has occasionally got me into trouble). And since my early schooling was in Spanish, a language came to me as easily as my native Engish, life among the Latins was where I felt at home.

Which was why, not long after I was married, I decided to abandon attempts to make a life for myself and my growing family in what was then Swinging London - no place for a young mother with babies (four under seven). So when it occured to me that a writer such as husband Nicholas could take his work anywhere, I thought I’d found the perfect reason to settle down in a house in a cork-oak forest in the wilds of Andalucia. Children are spoiled rotten among the Latins, local schooling would give my children what had made their mother happy as a child. And the soft lilt of the Andaluz regional accent reminded me of kindliness and delicious food unavailable to diplomatic daughter incarcerated for months at a time a damp English boarding school where mince-and-tatties was the Monday treat.

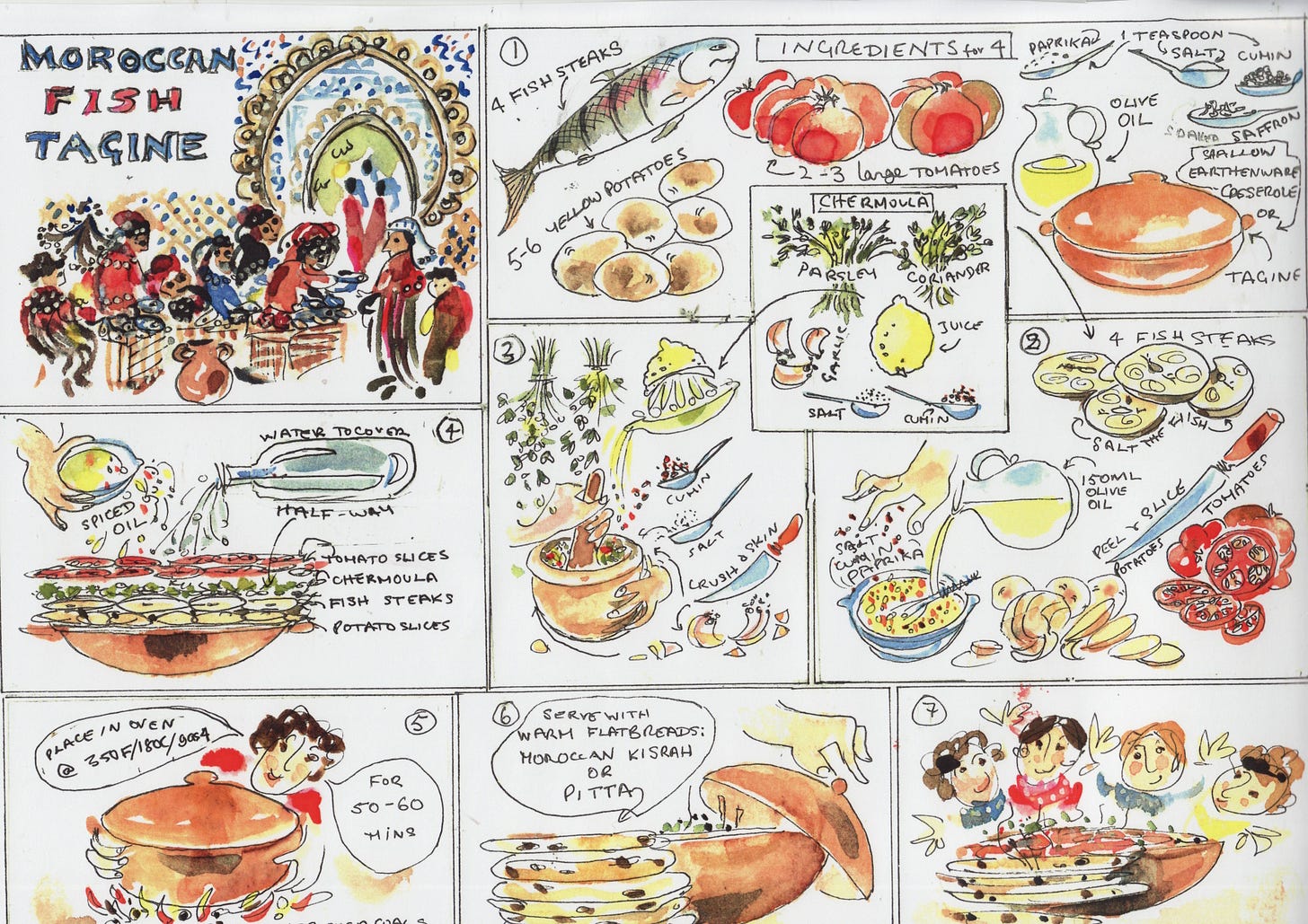

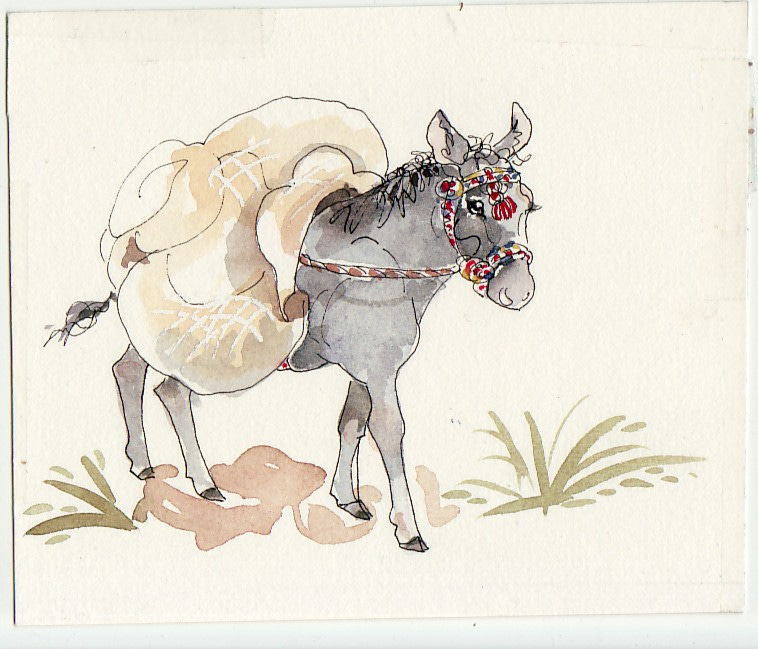

Once established in our newly-built family home in the middle of a cork-oak forest in a remote valley in a part of Andalucia where the Moorish influence was still strong, my neighbours were happy to show a foreigner who spoke a common language how things should be done. There had to be a pig to eat up the leftovers and a donkey to convey the children to school. Things worked out in the way that things do - as a learning curve for everyone, bumpy in parts but mostly sunshine - a story I’ve already written in Family Life - Birth, Death and the Whole Damn thing.

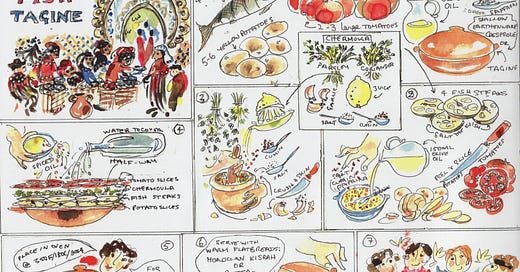

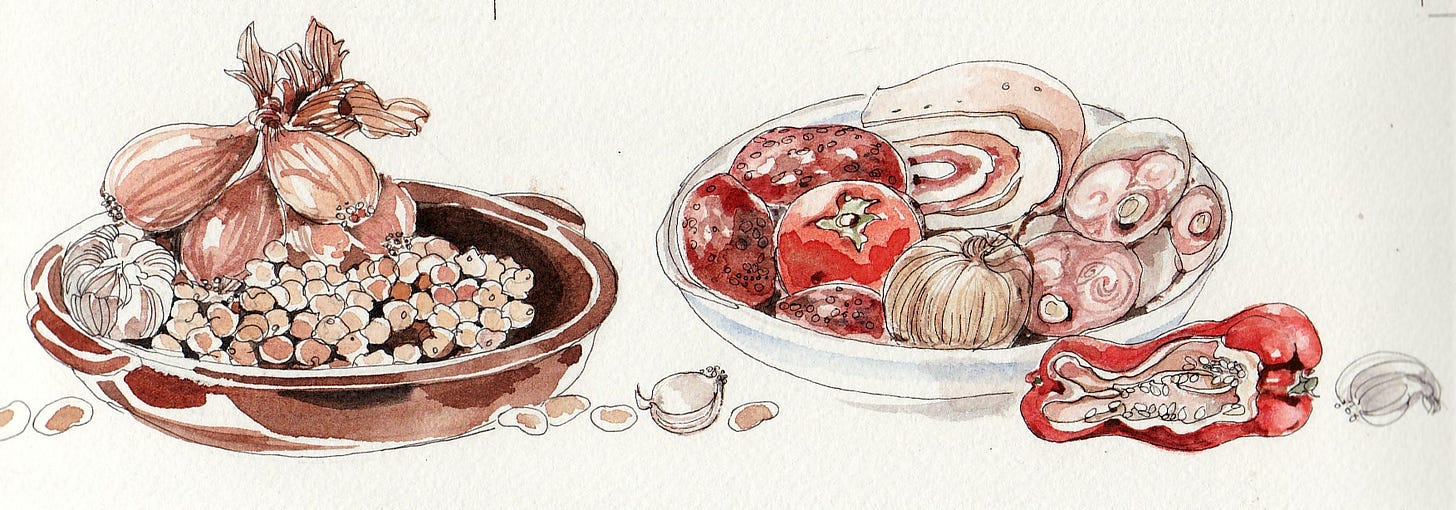

Family outings for passport-stamping didn’t usually include Nicholas: the call of the wilds of Andalucia proving somewhat less seductive than the bright lights of London. So we would take a day off from school every three months and board the ferry in Algeciras for a morning’s shopping and a midday couscous in the Tangier souk. Back home there was a basketful of tiny, fragrant packages - cumin, cinnamon, peppercorns, saffron - to perfume our Andaluz puchero, a one-pot soup-stew that takes it’s name from the original earthenware container, and is cooked and spiced in much the same way as Morocco’s tagine.

After our time in Andalucia was over, I didn’t return to Tangier until the mid-1990’s. With the children grown and gone, I had been travelling throughout Europe (in a camper-van, the only way to travel) with an Australian film-crew preparing a 13-part series based on my first serious cookbook, European Peasant Cookery. Morocco was something of a detour, but I wanted to make the point that travel between the shores of Mediterranean at both ends - Istanbul in the East and the ports of Andalucia in the West - was far more important as a cultural influence on Europe than is obvious from what is usually understood.

On our time in the region, I’d always bought my supplies of couscous as ready-mades - tiny grains that looked and tasted like a diminutive pasta and were weighed to order from an open sack in the souk. By the time I left the region in 1980, everyone who prepared couscous (including me) had switched to a commercial version that came in a packet and could be cooked rapidly, much like ready-cooked rice. Preparation of the grains by hand is time-consuming and demanding, requiring an understanding of how the grains behave when shaken in the air to coat in flour, which can only happen after you’ve mastered the exact art of rolling tiny nuggets of paste around a single grain of semolina (the hard core of a wheat-grain) to fit the holes in the sieve. Right. I’m glad we’ve sorted that out. Or maybe not.

Happily for the Aussie director of the tv series, Carmelo Musca (Sicilian, and no, he absolutely didn’t want us to go to Palermo and film his nonna), and his trust in my ability to know what we were looking for and why, on the day we were scheculed to shoot the preparation of a tagine to serve with couscous, a miracle happened. A small group of ladies spotted working together in a shady corner of the medina, an open space in the middle of the souk where people gather and talk, were doing exactly what was required. Better, still, they were willing to demostrate how it’s done.

p.s. The above video-clip was filmed in the Tangier souk in 1992 for The Rich Tradition, a thirteen-part series made for SBS Australia and BBC2. You’ll find the full half-hour - and all the other episodes filmed throughout Europe - at www.talkingoffood.com. The series was based on my first (serious) cookbook, European Peasant Cookery: first published in 1985 (first US edition, The Old World Kitchen) and still, happily, in print.

p.p.s. Beloved paid-subscribers will shortly be provided with a recipe for a seven-vegetable couscous bin tajine, a family dish just in time for the party season.

Hope you enjoy the couscous-rolling video-clip - so happy to find it! There's a ouarka-dabbing section in the same vid.

I learned to roll my own, so soothing. My first time was helping Paula Wolfert prepare for a class in California. Then in Trapani.