It's truffle-time in the Sienese hills. The season for Tuber magnatum, the rich man’s truffle (magnatum, of-the-magnate - sounds about right) runs from late September till the end of January, just in time for the fasting supper of Christmas Eve. The white truffle, as I’m sure you know, is at its most exquisite when finely slivered over hot buttery all-egg tagliatelli.

My guide to truffle-territory, Paolo, tartufai. is the proud owner of three prized truffle hounds, Lila, Suzie and Jessie. We meet in secrecy as the sun rises over the rolling hills of Tuscany. Paolo is of soldierly build, heavily moustachioed and dressed for the chase in English tweeds with leather elbow-patches. I have been delivered by taxi to an unmarked crossroads. and abandoned by the roadside. Paolo arrives fifteen minutes later with a squeal of brakes and his hounds bouncing around in the back of his truck.

As we bump along the track, Paolo expresses firm views on how the prize, should we be fortunate, be cooked. The dishes which suit the magnificent Piedmont white, tartufo bianco - a tuber which fetches three times the price of the Perigord black, T. melanosporum, its nearest rival in the money-stakes - are those that underline the flavour without masking the fragrance.

Unlike melano’s crumbly, more robust flesh which can be grated or sliced and stands up to the heat of the fire, magnatum must be treated with far greater delicacy, never grated but finely shaved with a sharp blade into delicate ribbons and dropped directly onto something hot and slithery: fresh pasta dressed with butter, or a risotto prepared with dried porcini and a grating of one of lesser species such as T. aestivum which can be mistaken for melanum, or T. borchii – bianchetto, a spring truffle which, though smaller and browner, could be mistaken for magnatum, though certainly not by Paolo.

Licenses to hunt truffles in Italy are awarded on completion of a written examination and are legal only in the hours of daylight. Night-gathering is punishable by a heavy fine. The reason for secrecy, however, is not that we might be acting outside the law by heading so early for the truffle-grounds, but because of the threat posed by dog-knappers. A truffle-hound, however clever, is only likely to be successful in his own terrain. Among breeds most likely to respond to training are cross-bred dogs - bastardelli da pagliaio, haystack mongrels - with a high proportion of setter, spaniel, terrier, retriever and poodle, the German hunting-dog.

Dog-knappers are more to be feared than truffle-thieves. A good dog is money in the bank and can never be replaced. A truffle is only a trade-item, sold for money, eaten and forgotten. Truffle-hunters don’t eat their own finds, any more than people who work in chocolate-factories eat chocolate.

To choose within a litter, continues Paolo as we head into the undergrowth, there is always one puppy, usually a bitch, who’s more curious than the others. I take notes on the back of my sketchbook as we bump along the road. First, you need a dog with enough intelligence to be curious. Next, well, everyone has their own method of training, but what’s needed is patience. A dog needs encouragement. Paolo’s training method is to show a new dog a scrap of truffle and see if he wants to smell it. Then the trainer buries a few bits of truffle, and if the dog digs in the right place, he knows she has potential.

We roll to a halt on a rough track which follows a spur of the crete seneses, a series of little eminences like upturned sugarbowls slashed with ravines of startling whiteness. Some of these little hills, calenque, were flattened long ago to make fields for the plough - laborious work with pick and shovel.

Along the track leading downwards towards a wooded ravine, magnatum-territory, are pairs of dainty little double hoof-marks.

“Cingale - wild boar,” says Paolo. He is not pleased. While the presence of wild boar is an indication of truffle-territory, pigs count as the competion. Furthermore, he adds disapproving, these particular cingale are rutting and the smell distracts the dogs. The dogs - even Jessie, the newcomer – appear to be undistracted, set off enthusiastically through the undergrowth. Noses down, tails wagging, they arrive at the bottom of the slope and begin to scrabble around in the sticky red earth of the stream-bank.

Botanically the truffle is a hypogenous fungus, an underground mushroom which fruits, as do others of its kind, on a fine web of filaments which attach themselves to the roots of certain trees. The relationship is symbiotic - of benefit to both parties - rather than parasitic, though at the moment of fruiting, the tree-root provides the nourishment and the exchange becomes one-way. There are hundreds, possibly thousands, of truffle-species on every continent, only a handful of which are good eating and some taste downright nasty. While the Perigord black is relatively easy to cultivate and is in production in Australia, New Zealand and the States as well as Spain (since the 16th century) and France, the Piedmont white has proved far more difficult - actually impossible until very recently, and only in small quantities from inoculated poplars carefully hidden in secret valleys in regions where it’s already at home.

Ecologically the white is a lot pickier than black, occurring in the wild only in a mountainous slice of northern Italy, a small patch of Provence and a modest slab of Croatia. While the Perigord black is relatively adaptable, needing little more than marginal land, chalky soil, plenty of light and a suitable host-tree, the white needs a tailor-made eco-system with the right amount of shade, a variety of supporting bushes and soil of a specific lightness which can only be achieved by an annual process of agitation such as that delivered by minor landslides, flooding, incomplete ploughing and, as we can hear from the rumble of heavy machinery on the far side of the ravine, regular movement of earth when road-building.

The territory is right, the dogs are eager, omens are good.

Paulo leans on his walking stick and lights a cheroot. Italians smoke like chimneys but it doesn’t seem to make a difference to their ability to appreciate the aroma of a good wine – Barolo, in these parts - or Piedmont white in full fragrance. Paolo’s truffle-dogs are trained in the field. This is not easy to achieve. While the tradition round the Mediterranean in mountain areas where there’s no cultivation is open access to all, gatherers and trufflers alike. There exists, however, a code - sometimes established in law, sometimes not - as to where you may or may not search. But since one gives any information about where they hunt successfully and the crop is both random and secret, you need to know the rules of the locality.

Paolo knows the locality, has made his arrangement with landowner, and his dogs are trained to the territory. Dogs are bonded to the terrain as strongly as sheep or cattle. They don’t like unfamiliar places and are capable of returning home even if transported hundreds of miles from their hunting grounds. A kidnapped dog will not perform as successfully anywhere but in the territory he knows. Dog-knapping may well be profitable enough to attract the attention of criminal gangs, but the purchaser can’t be certain if the dog will deliver, still less if, released from confinement, the ungrateful mutt won’t simply turn round and go home.

Lila, veteran of the truffle-trio at twelve years old, finds something of interest to scrape at in the soil beneath a poplar, the commonest host for the Piedmont white. A good dog can pick up the scent of a ripe truffle at well over a hundred metres, however deeply it’s buried.

I crouch down to join the inspection party.

Lila waits expectantly for the short length of breadstick which is her reward. An intelligent dog such as Lila will measure the length of the breadstick at the beginning of the hunt and losing interest when it’s finished.

Paolo gently pushes the dog aside, rubs his fingertips in the loosened earth, lifts the digits to his nostrils, inhales deeply and stetches out his hand.

“Anything familiar?”

The fragrance is unmistakeable. One sniff and I remember my last encounter with the precious tuber - exactly where and when and with whom. This has nothing to do with the attraction of the scent – that goes without saying – but is a deliberate survival strategy by a spore-spreader which spends its entire reproductive life underground. To attract a predator, the truffle must be memorable. There’s no point in being the most delicious foodstuff in the wildwood if no one knows where to find you. The truffle-mycelium is slow to fruit – seven years for the black, double that for the white – and produces hereafter once a year and only when conditions are right. To counter this shortcoming, the truffle is endowed with a memory-trigger - an effect identifiable on a human brain-scan – which ensures its predator remembers location and timetable. Simple, really.

Hedgehogs like it too, says Paolo, indicating a patch of scrapings nearby. What with cingale and hedgehogs, it’s a wonder there’s anything left to find.

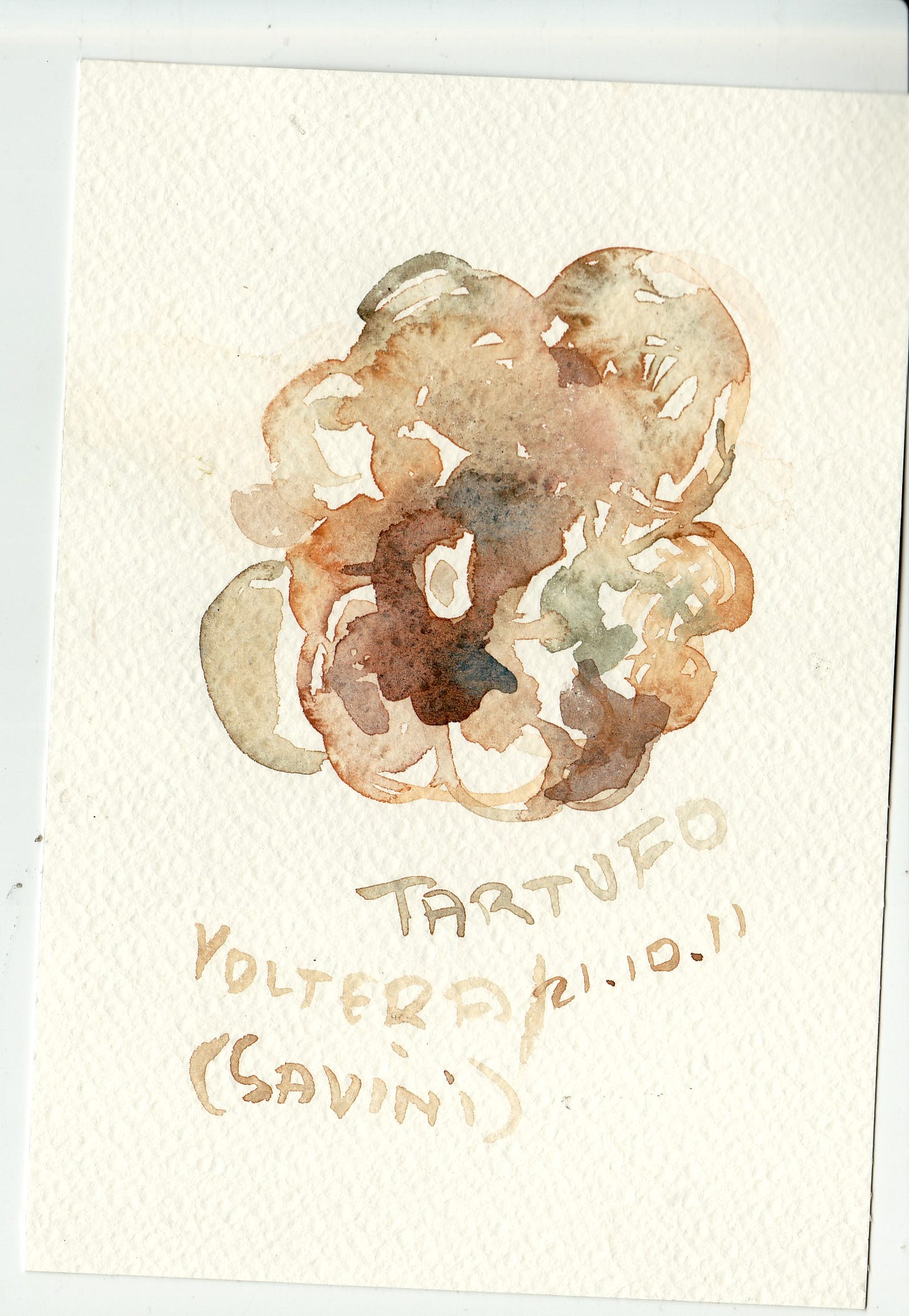

As Paola scrapes at the loosened earth, a smooth brown lump the size of a large marble comes into view. The lump has created a little subterranean bed for itself, like a diver’s capsule. Paolo lifts it gently, releasing a whiff of petrol-scented air. The truffle is past its best. A gleaming trail of snail-goo bisects one corner. Snails hibernate underground in winter, tunnelling deep into soft earth and taking advantage of such subterranean treats as come their way.

Lila receives her reward in spite of her master’s disappointment. A truffle-dog should never be beaten, never discouraged if the hunt fails, always rewarded when successful.

When accompanying a truffle-hunter to observe how he works, as is our agreement today, there is only one rule: pay no attention to the dogs. Don’t pat them or make a fuss of them or they’ll think you have food and lose all interest in the hunt.

I keep my hands firmly in my pockets.

The dogs move off up-stream, snuffing through the undergrowth and the sticky reddish mud of the bank. The water is low, exposing a thick margin of cracked earth.

Jessie takes the lead, her enthusiasm as newcomer promising well for future finds. A young dog will keep going for longer, but an old dog knows more and will serve as instructor, back-up to the master, in much the same way as older siblings take charge of the youngsters.

Certain dogs are suited to certain terrains. In France, where the truffle-terrain is dry and sandy, the dogs for the job are small patch-coat terrier-types with delicate paws vulnerable to over-use. In France, a truffle will call a dog to heel immediately - a truffle-mutt with sore paws won’t hunt. In Italy, the canine for the job is the largato romano, a curly-coated poodle-spaniel of medium size and stocky build bred as bird-dog, picker-up, since the 16th century by the wild-fowlers of the Ravenna lagoon.

The poodle-breed is the German hunting dog bred for the forest, while the spaniel is a retriever, bred to fetch and carry in wetlands. The mix of the two, along with a splash of terrier and a drop of setter, produces the perfect cross-breed for white truffle terrain – woodland with stream-bed.

Jessie, the two-year-old, splashes in and out of the water, shaking herself vigorously all over Paolo’s gentlemanly tweed jacket. I jump smartly out of the way to avoid a soaking. Paolo shrugs indulgently and brushes himself down. Young dogs will be dogs, what can one do?

A truffle-dog is in her olfactory prime between five and eight years. After that she makes up in wisdom what she lacks in energy. A talented dog has an easy life - not always the way with haystack mongrels - and can expect to live to a ripe old age.

Susie, the middle dog of the truffler-trio, is six years old and in her prime. She halts beneath a young oak-tree, pawing hopefully. Susie is not averse to a bite of truffle herself. Although the Piedmont white has its own flavour characteristics - earthy, garlicky, flowery, tasting of parmesan - the real value lies in that inescapable fragrance of, not to put it delicately, sex. Whatever the attraction of a truffle to a dog, Susie gets it. But she’s the only one of the three who prefers truffle to bread.

Paola follows Susie. I follow Paolo.

Susie loses interest when Paolo pulls her gently away, and Lila, the wise one, takes over.

Judging by vigour of the tail-wagging, there’s something here. Dogs are essential to the hunt for magnato. The Piedmont white comes to maturity without warning - overnight if the weather is warm for the time of year - leaving the hunter no chance to identify its presence in advance. The Perigord black, melano, takes up to three weeks to produce full fragrance, allowing the hunter to pinpoint its location and return with or without a dog at the moment of optimum ripeness. Once lifted from its bed, the white loses bulk and fragrance within 3-4 days, while the black retains most of its characteristics for a fortnight. Both are at their best when freshly lifted from the earth, as now.

Paolo straightens up in triumph. The tuber, when delicately released from its cradle of damp earth, is a magnificent spherical beauty at the moment of perfection - Helen of Troy as first spotted by Paris. See? It works. The scent, as it reaches me from a distance, is sweet and flowery with an after-fragrance of hazelnuts and that indefinable something which is irresistible to all but – well, not even a snail can ignore its attraction.

“Fabuloso,” says Paolo, holding out the prize wrapped in a scrap of snow white linen produced from a pocket like a rabbit from a hat.

I accept the offering, inhale deeply and hastily hand it back. The scent is so powerful it makes me giddy. My reaction to a vigorous truffle-hit has always been a little embarrassing. The first symptom is a wild sense of excitement followed by a rapidly beating heart and measurably-raised blood pressure - the real reason, it so happens, for the truffle’s well-known reputation as an aphrodisiac. Raised blood pressure is useful under circumstances I’m too dainty to mention.

When sliced through to reveal the delicately-marbled interior, the flesh of magnatum is compact, elastic, pale, silky and velvety to the touch. Paolo explains that the colour varies a little according to the host – there’s an ivory tinge for poplar, reddish for oak. This particular beauty has a delicate russet tinge to the skin which is fine-textured and smooth as an eggshell. Melano, on the other hand, has a dark, patterned interior and a lumpy, roughish black skin.

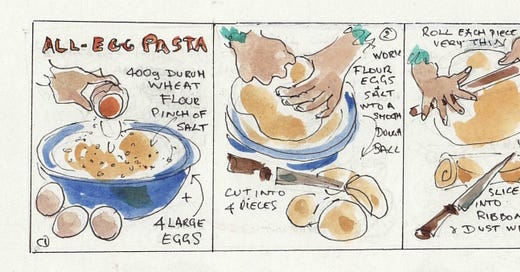

No professional tartufai consumes his own gatherings. Magnatum is reserved as a trade-item, sold by the poor to the rich. When pressed, however, Paolo admits that in a good year he might keep one really good one to eat on freshly made pasta with the family on Christmas Eve, when meat is forbidden. For this special meal, Paolo's wife, Caterina (called for the de Medici women), makes a fresh batch of taglionini using only egg-yolks and fine white flour, grano duro. And when the pasta is just tender and not too well-drained, it’s tossed with a little sauce made with mascarpone, white wine and butter and seasoned with nutmeg and grated parmesan.

Paola smiles dreamily, re-living every moment.

When the pasta is heaped into hot plates in which has been melted a little butter, one for each person - then, and only then, is the pasta ready to receive its truffle which must be sliced with the greatest possible care with a specially-sharpened knife which is kept for no other purpose. You may grate the black, the Perigord truffle or the English truffle, the one the French call truffe de bourgogne, but magnatum must never meet anything but a sharpened blade.

Whatever you have, and no one can be sure of what will come to hand, the pasta must be hot and freshly dressed so that the truffle releases its fragrance on the instant and is eaten without delay. If you follow these rules on Christmas Eve, says Paolo, you will dine like a new-born king.

p.s. Beloved paid-subscribers will shortly be in receipt of delicious things to be done with the rich man’s truffle. Anyone can dream!

What a lovely post…and downright hilarious too. Thank you.

Reminds me of my white truffle foray in Alba with Jane and Geoffrey Grigson. See "Out to Lunch"