Right now, at midsummer in the rose-fields of Isparta in south-west Anatolia, it’s all over till next year. Anatolia, as I’m sure you know, is the whole of Asian Turkiye, a vast plateau into which you could fit the whole of France with room left over for Switzerland. Fertile with an underlying watertable, prone to earthquakes, it forms the western corner of what’s generally known as the Fertile Crescent. If geography, latidude and trade-routes dictate how people live, the Fertile Crescent is where our ancestors began the long journey to what we haven’t yet achieved - a settled population, peaceful and prosperous, respectful of nature, tolerant of those with whom we share the planet. For hopefulness’s sake, call it a work in progress.

The rose-fields of Isparta, a prosperous trading city that proclaims its interest through ten-foot high, multicoloured, plasterwork posies set in roundabouts along the central boulevard, are in full bloom from the beginning to the middle of June. Which is why, a couple of weeks ago, I was on the road with good friend and fellow food-writer, Gamze Ineceli, Istanbul-ite, authority on everything gastronomic in Turkiye with a particular interest in the traditional cooking of the villages of Anatolia.

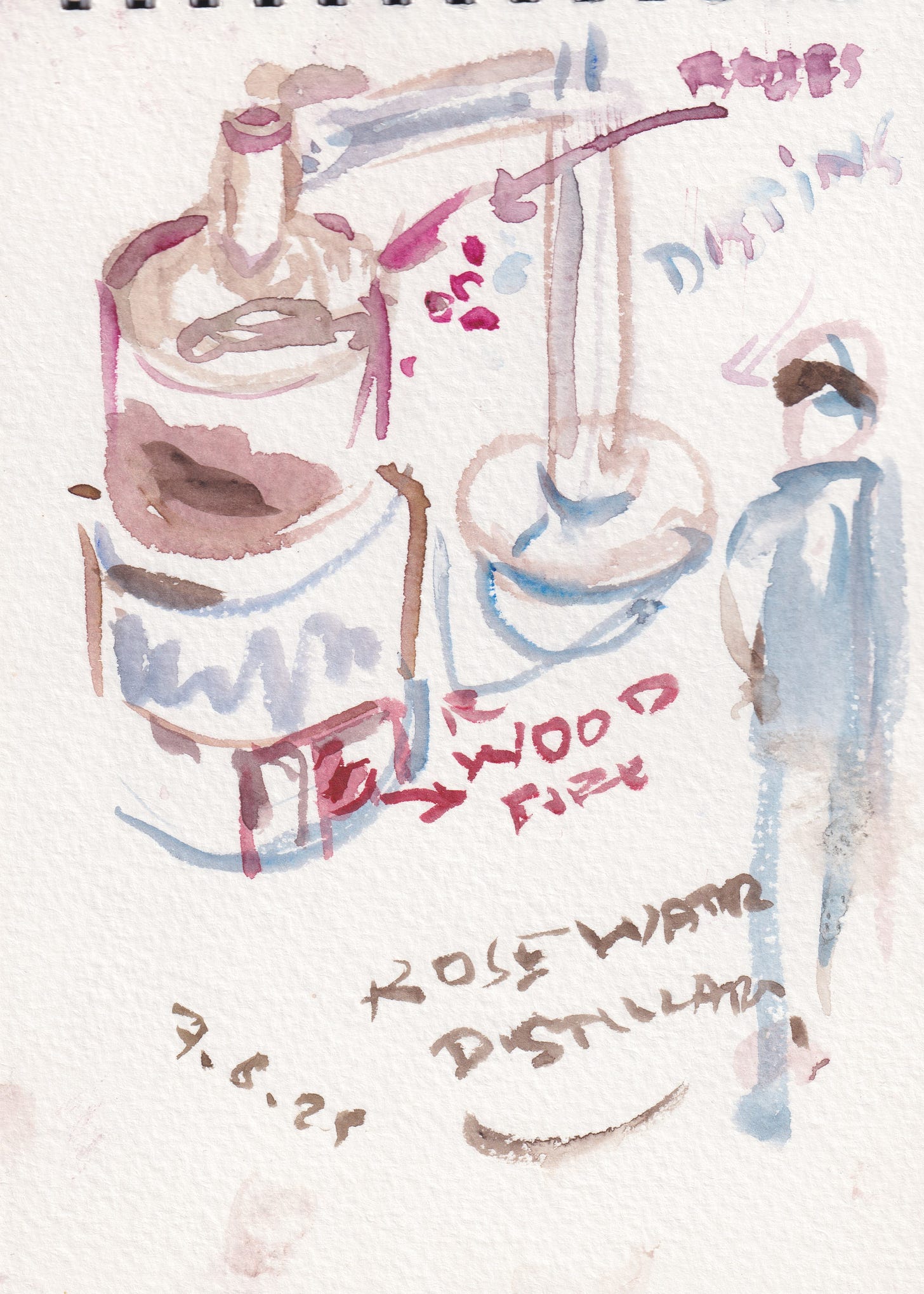

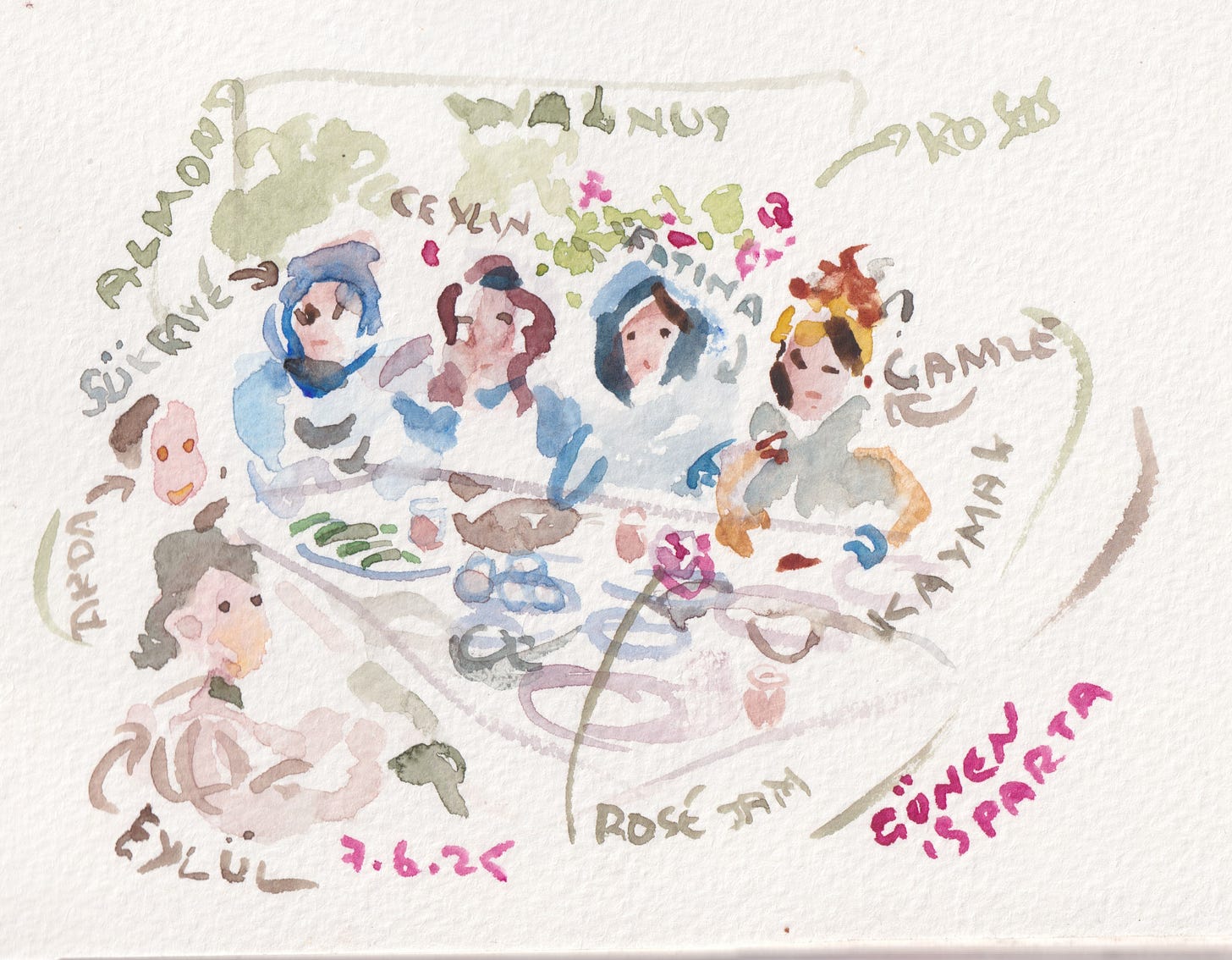

We’ve been working and travelling together on a project (of which more later). And while I don’t speak Turkish, a gentle-sounding language with its roots in India, I communicate wherever I don’t have the language through my sketchbook and paints, a friendly way of exchanging information between those who know and those who don’t, particularly if the subject is ingredients in the marketplace and how to cook at home.

As soon as we arrive at our first destination on this particular trip, the rose-fields of Isparta, our hosts, Ugur Ozdel and wife Sükriye, have been hard at work since sunrise. Perfume-roses are their most fragrant in the early morning and must be weighed, delivered to the distillery for processing within the day. Today the harvesters are on catch-up. Yesterday was a national holiday, Kurban Bayramı, otherwise known as Eid Al-Adha, one of the two most important festivals in the Muslim year, and the roses, left to their own devices, have put on an extra day's growth. Roses wait for no man or woman. Most of the pickers are women. The work is seasonal, conveniently limited to the early morning, and provides much-needed extra cash for a farming household.

"We’re all local,” says Sükriye, pushing back her straw hat and waving to a couple of harvesters swathed in sun-protecting garments working among the bushes. “We don’t do casual labour. The work is too specialised. And anyway, it’s a source of income for our neighbours as well as a business for the family. There's competition, of course, from the big commercial growers, but the quality is not as good, and people know it."

The gatherings are paid by weight. Sacks of the morning's crop is taken straight from the field to a white-washed building in the middle of the rose-fields to be weighed on a hand-held Roman scale - a chain-handle with a weighted hook that’s as accurate today as it was two thousand years ago. The bulk goes straight to the distillery, with the most perfect petals set aside for rose-jam.

The distillery is close - the blossoms must processed immediately before the fragrance fades - a simple one-room shed among others in a commercial area beside the main road, past fields of snow-white opium poppies grown for the medical trade and swathes of scarlet field-poppies in every ditch. At the distillary, the petals are tipped straight into a copper vat set in a concrete sleeve, heated with water to evaporation-point by a wood-fuelled furnace, and continue onwards in the form of steam through a water-fed cooling tube, re-emerging, after a second distillation, as precious droplets of attar of roses, rose-oil. Simple. All you need is a rose-field in bloom and a few centuries of know-how.

The perfume-rose, Rosa damascena, Damascus rose, is a bush-rose first cultivated in China (probably), established in the gardens of the Persian Empire, planted in the valleys of Bulgaria under the Ottomans, found itself an outpost in the hills of Provence, and headed back to the fields of Isparta, where climate and altitude have long suited orchards of peaches and apricots, fellow members of the rose-family.

The rose-fields of Isparta produce atar of roses for the perfume and cosmetics trade, and culinary rose-water for perfuming lukoum, aka Turkish delight, sold freshly-prepared in specialist shops throughout the region. Among the most famous of these is the loukum-and-halva emporium in Afyon, an Ottoman town, where dozens of differen fillings are prepared daily, some with pistachios, or walnuts, or (most exquisite of all) rolled around a little blob of fresh kajmak - snow-white cream so thick and solid it holds its shape on the spoon.

Back in the rosefields, among the tidy rows of bush-roses, a few fruit trees have been allowed to self-seed, providing the occasional patch of shade in the morning’s heat. “We don’t use chemicals in the rose-fields," says Sukriye, pinching off a tangle of young bindweed that's wound its way through the prickly stems overnight. Families who've been farming the land for generations know from bitter experience that crop-control chemicals are not good for children - their own or anyone else's.

After the harvest has been weighed and sent off to the distillery, a mid-morning breakfast is ready to be set on the table under the vine-arbour. Everyone is hungry. The children sit down with the adults - Turks don’t do baby-food. Eldest of the next generation, 18-year-old niece Eylul, is aiming for a chemistry degree - very useful for the family business. Her younger brother, Arda, says he wants to be a baker when he grows up, an appropriate choice in a region where, according to the botanical record uncovered in Neolithic excavations at nearby Çatalhoyuk, the earliest of our modern wheat-varieties was brought into cultivation.

Baker's bread - light-textured and crisp-crusted - is set on the table along with a plate of just-boiled eggs to be cracked and shelled and the obligatory bowls of spoon-salad - chopped tomato, cucumber and mild white onion - that appear unbidden with every meal. Everything, mostly home-grown, is set on the table for people to help themselves. There are too, slices of salty white curd-cheese and finger-length rolls of stuffed vine-leaves - a rolling technique nimbly demonstrated by Ugur with a fresh vineleaf, to applause and laughter. And. the star if the show, a dish of kaymak, the thick white cream so pillowy and firm it’s impossible to resist.

"You must eat it with our rose-petal jam," says Ugur, spreading a generous spoonful of snowy gloop on a chunk of bread - nothing dainty - and topping it with a shiny heap of rose-petals set in scented syrup.

Attar of roses, rose-oil, produced by a process of evaporation in much the same way, using the same equipment, as Turkish raki or Scots whisky or any other spirit. Pure rose-oil is valued by the perfume and cosmetics trade not least for its healing qualities, something well-understood by Ottoman princesses.

Rose-water, on the other hand, is a far simpler process, a matter of steeping freshly-picked rose-petals repeatedly in water till the perfume is transferred, as explained by Georges de Maudit, native of Provence, in The Vicomte in the Kitchen in 1934, the heady days between the two World Wars.

'To prepare rosewater, soak rose-petals in a silver bowl in enough cold water to cover, leave for an hour, strain and repeat with fresh petals as many times as required, then bottle and store in the fridge.”

Vicomte de Maudit’s Rosepetal Jam

Gather your roses before sunrise on a dry day, advises m. le vicomte, inspect each petal for bruising and remove the little white point at the center. Allow one litre of rose-petals to an equal volume of water to the same weight of preserving sugar to the juice, pith and pips of a lemon, and cook till set.” No further instruction is offered or needed. Monsieur de Maudit was a plain-talking soldier, somewhat too plain-speaking, as it happened, since he spent a couple of months in pokey in London for bad-mouthing the authorities in 1941 by making statements 'likely to cause alarm or despondency’. ‘Twas ever thus.

p.s. You’ll find the Ozdel family’s website at https://www.gonengul.com

p.p.s. Beloved paid-subscribers will shortly receive recipes for rose-vinegar, rose-and-raspberry shrub, and (the cherry on the proverbial cake) Gamze's chilled rose-water pudding.

Really engaging and informative.

I also love your watercolour sketches of each process in the rose petal distillation for rose-oil or the recipes for rose-water and rose syrup.

Thank-you.

Currently in Homer, Alaska, the wild roses are in bloom and this year seems to be the most spectacular I can recall in 42 years! Everywhere you look there a many roses in bloom. I adore them so, their beautiful deep red pink when first opening, to their soft baby pink when in full bloom. Their delicate subtle fragrance can be delightful if there is a breeze blowing your way on a warm day. I told my husband I hope I pass in June when the roses are in bloom and can join them in the field. Thank you for a wonderful story Elizabeth!