Talking about Christmas in Provence

...Monsieur Weber sorts it all out with Mademoiselle Paulette

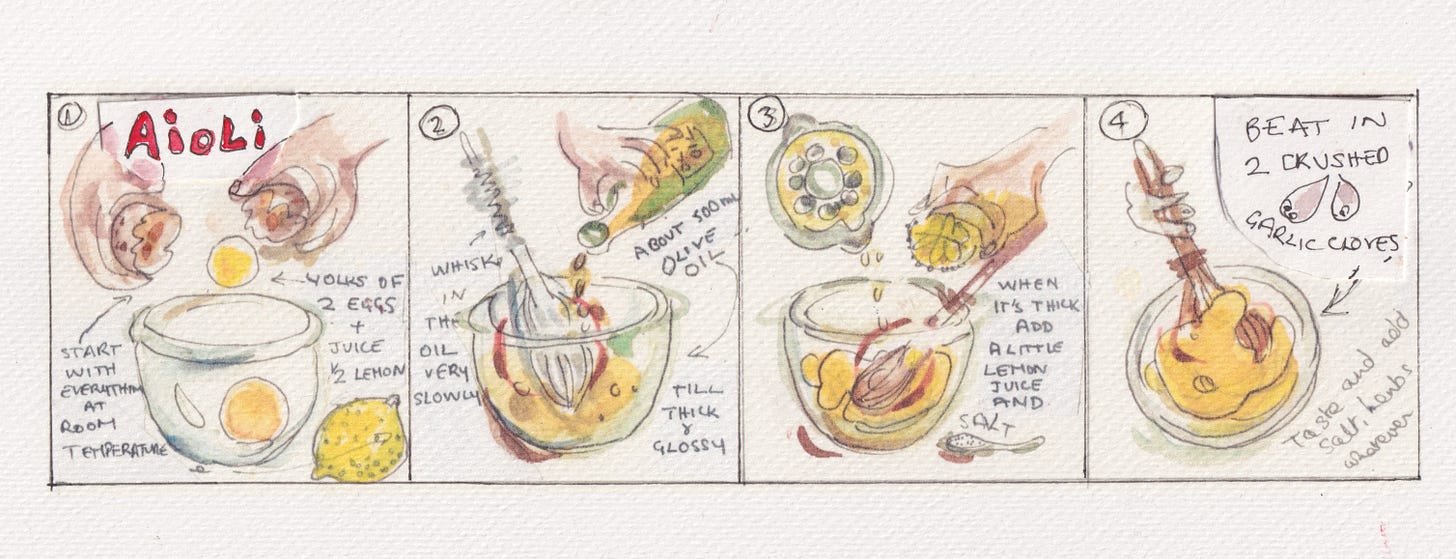

Aioli - just garlic and oil in its original incarnation - is thick spoonable sauce of olive oil emuslified with garlic pounded with salt. In Province, where olive oil and garlic are a way of life, it’s used in much the same way as butter in the rest of France, as an enrichment for plain cooked foods or on its own with bread. Nowadays the usual thicker is egg-yolk, as for mayonnaise, which makes the sauce more stable. It is, in either case, a rich dish suitable for celebrations such as Christmas.

In the olden days - which as far as I’m concerned, was before my four children untied the apron strings and made their own lives elsewhere - I would beg, borrow or rent a Christmas house in unfamiliar territory. This was partly because the excitement meant there was little time for family quarrels, but mainly because it was the perfect opportunity to learn how other people live.

The family favourite was Vaison-la-Romaine, a hill-town in Upper Provence. The house’s owner, Monsieur Weber, headmaster of the local secondary school, was from Alsace. As an incomer in the region, he took a scholarly interest in the traditions shared by his pupils. His mentor and guide was Mademoiselle Paulette, pre-school treacher in the ecole maternelle in the nearby village of Villedieu.

M. Weber, concerned that we, the English family who rented his house three years running, must surely be in need of instruction on how to spend Christmas in Provence. Mlle Paulette was of the same opinion. It’s a complicated business. It would be a tragedy is we were misinformed. A tutorial was duly arranged. Provençale traditions, we must understand, are not as practised in the rest of France. For a start, the old language of southern France and Catalunia, the lingua franca was langue d'oc, in which 'oc' means 'yes', while in rest of France, the langue d'oil, 'oui' is the accepted affirmative.

Those who spoke langue d’oc, the language and literatue of the troubadours, were brutally suppressed in the thirteenth century by His Holiness of Rome, with the assistance of an Englishman (such as ourselves), Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, for reasons of un-Catholic religious practices that, although nominally Christian, were duallist, vegetarian, and feminist, since women performed priestly functions, including occupying high office.

Meanwhile, those who survived the massacres - Cathars, Albigensians, Protestants - disappeared underground until, in the aftermath of France’s revolution, poet Frederic Mistral, revived (or re-invented) Provençale traditions for a new romantic age. Physical evidence - talismans, dried mole’s-paws, domestic implements, pots, pans, pictures, musical instruments - are housed in the poet’s legacy, Museon Darlaton, a fabulous folk-museum crammed (though lately re-curated, more’s the pity) into a handsome town-house in Arles, just around the corner from Van Gogh’s Night Café. Among its many joys is, or possibly was, a magnificent waxwork panorama of the fasting supper of the Eve, La Souper Maigre, .

The history lesson concluded, Mlle Paulette and M. Weber are in complete agreement on the Christmas timetable, though the meal can be considered variable. At 7 o'clock on the Eve the yule log is lit in the fireplace, possibly with a libation of red wine. Although if the house is centrally heated (as is M. Weber’s), the real log can be replaced with a buche de noel, log-shaped cake covered in chestnut or chocolate icing (or both) displayed on the sideboard.

The meal is eaten in two parts. Fast before feast - as is usual on important feastdays - is divided by a visit to the church for Midnight Mass (in thought if not in practice). The first meal of what will carry on until morning - not for the fainthearted - is the Souper Maigre, fasting supper. This includes no meat, no wine, no sweet things and nothing but water to drink. After midnight comes Reveillon (roughly translated, ‘wake-up’). The menu - roast birds, maybe goose-liver, foie-gras, prepared in house, and a truffle or two found beneath the lime-tree, tilleul, planted in the yard to supply the household with its digesive infusion. No one can say that one choice of menu is correct and the other is not. Which is just as well. No one wants fisticuffs at dawn on Christmas day.

M. Weber's Souper Maigre:

In Vaison, it’s usual to serve a soupe aux lasagnes: prepare a broth with carrots, leeks and a bouquet garni and add torn pieces of pasta - a special kind with frilly edges as a reminder of the new-born Infant’s curls. On the table a` decoration, a little dish of sprouted lentils with curly stalks.

The main event, also meatless, is cardoons with an anchoiade, salt-cured anchovies crushed into warm olive oil. ]To prepare cardoons, trim off the all bitter leaves, outer and inner, and cook in water till just tender. To prepare as a gratin, drain, chop, toss with a little flour and olive oil and make a little sauce with white wine and few of the little wrinkled black olives of Nyons cured under snow, spread in a gratin dish, sprinkle with grated cheese and brown under the grill.

Mlle Paulette's Souper Maigre:

Villedieu, on the other hand, prefers Le Grande Aioli: a big bowl of garlic-and-oil (with or without egg-yolk) served with a magnificent array of plain-cooked winter vegetables (possibly including cardoons) eaten with plain-cooked salt-cod (or possibly seared in olive oil with garlic). For those who can’t afford salt-fish (expensive) can replace them with snails cooked and turned, shells and all,, in a white-wine bechamel with shredded chard, blea, a hardy leaf-vegetable for which the Provençaux are known to be so found they’ve earned themselves an indelicate nickname, caga-blea (no explanation necessary, much appreciated by the teenagers).

Mlle Paulette's Reveillon

The most important of Provence’s festivities (found nowhere else in France) is the setting out of Les Treize Desserts, Thirteen Desserts. These are not as might be supposed, a marathon bake-up by the cook, but twelve little dishes of ready-prepared good things, one for each of the Twelve Disciples (still including Judas), with the Master represented by a sweet bread or apple-stuffed tart. Renewed daily, set out on a table by the entrance so visitors and children can help themselves, the arrangement serves a kind of open larder.

In the village of Villedieu, Jesus is represented by the pompe-a-l'huile, a sweet bread enriched with olive oil and egg and flavoured with orange-flower water, while the twelve disciples are represented, variously, by little bunches of muscat grapes gathered in autumn and hung from the rafters so they don’t dry out; William pears whose stalks have been dipped in scarlet sealing wax to keep them juicy; pommes reinettes, yellow-fleshed apples, crisp and fragrant, used in pies and tarts; dried apricots, locally cropped, evidence of careful housekeeping); quince paste, påté de coings, to eat with a sliver of goat's cheese; black and white nougat, the first prepared at home with honey and hazelnuts, the other factory-made in Montelimar.

In addition, imported from the land of the Infant’s birth, oranges, tangerines and dates from the Christmas market. Which is not overlook the beggar at the gate - any or all of the four begging-orders of monks arriving unannouced (as might Jesus himself) to claim the empty chair at the festive table: blanched almonds for the white-robed Dominicans, rough-skinned figs for the Franciscans, smooth brown hazelnuts for the Carmelites, and wrinkled currants for the Augustines.

As for the rest, feast after fast begins at midnight and carries on until dawn.

M. Webber's Reveillon

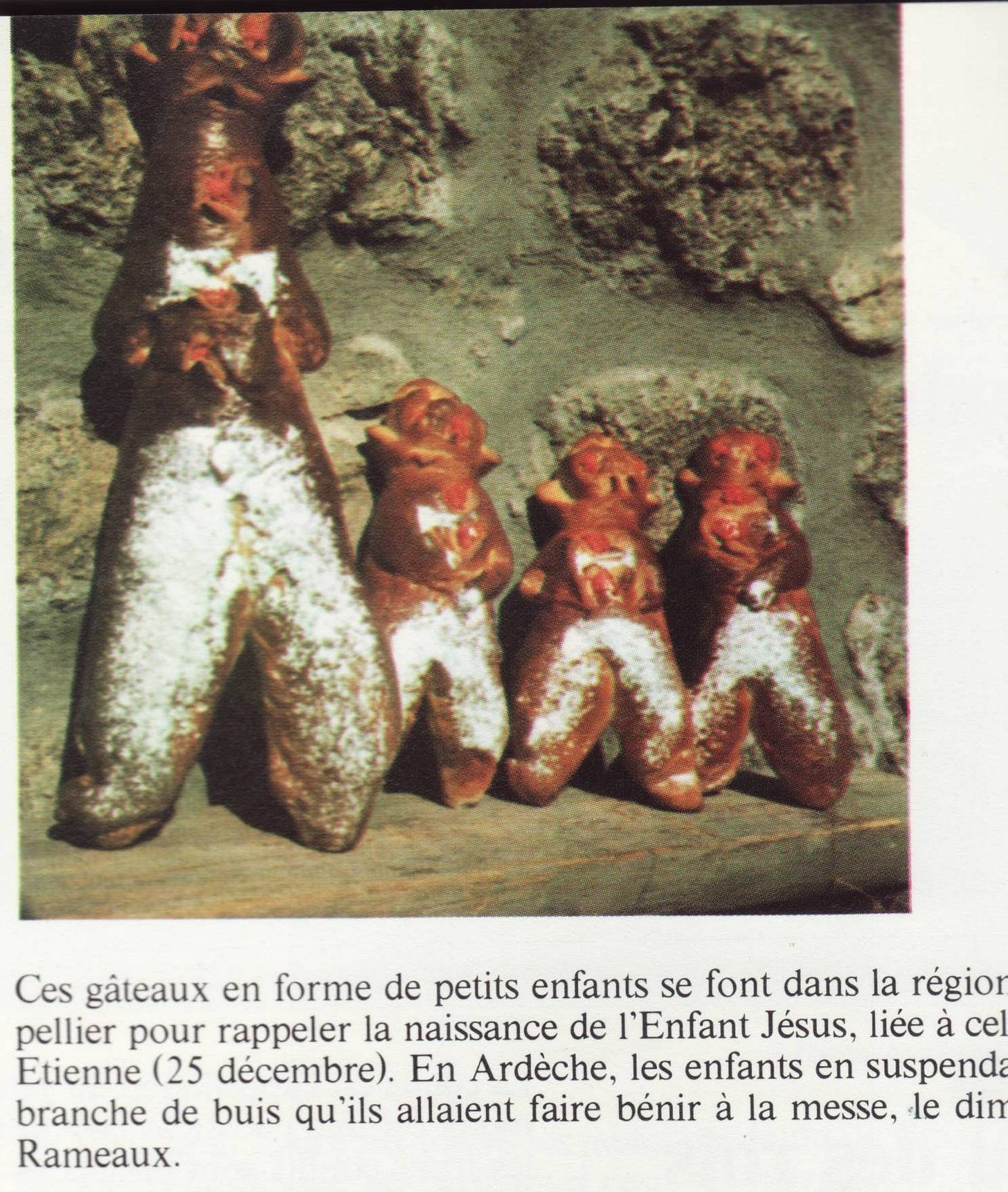

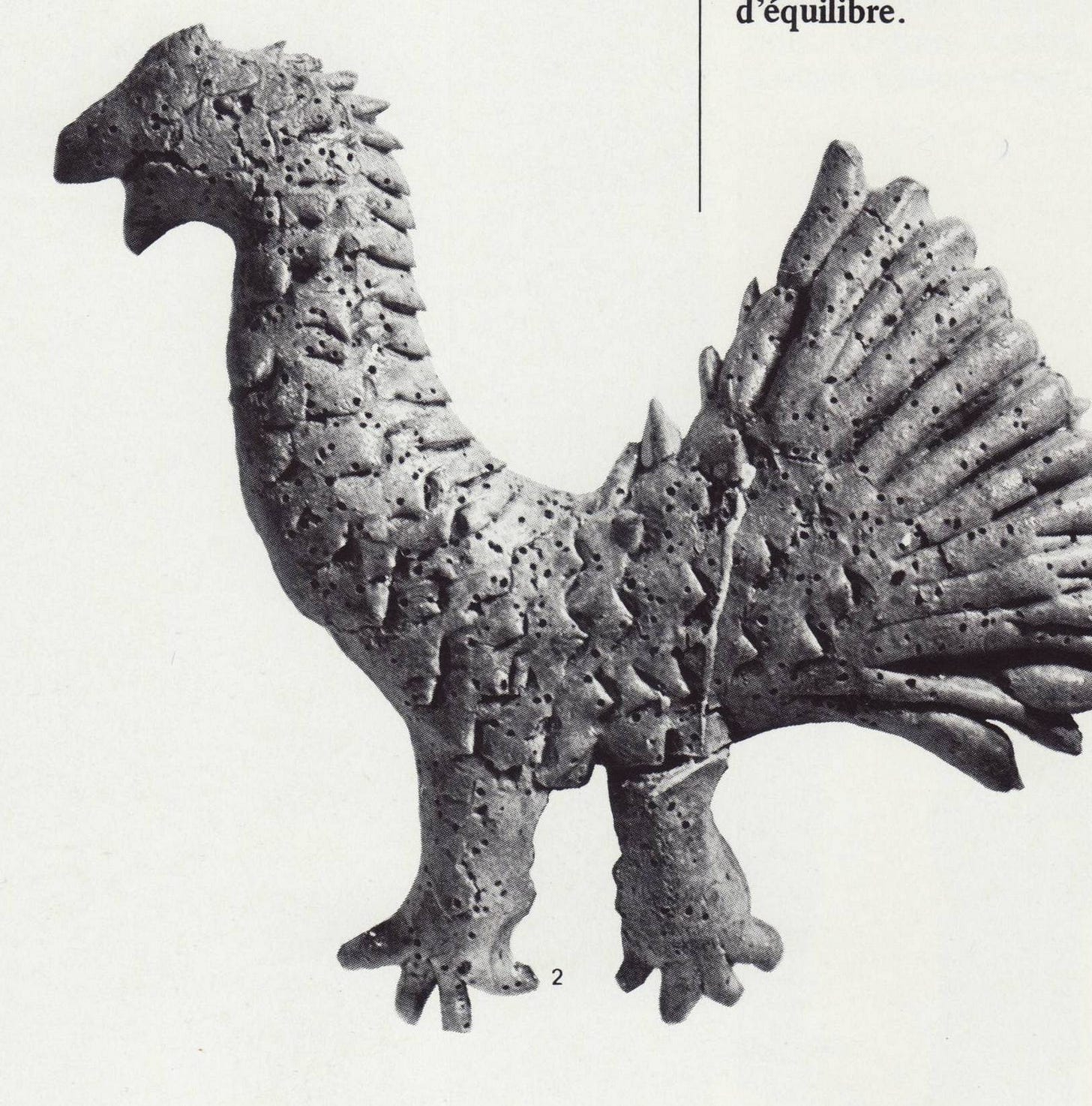

Mlle Paulette's pompe a l'huile may well be traditional in Marseilles, says M. Webber, but, in his experience in Vaison, it’s more likely to be fougasse, a leaf-shaped bread slashed along its length to resemble an ear of wheat, seeds being essential at festivals of renewal There are, too, traditions that must be observed if all is to go well in the coming year (though M. Webber doesn't believe in such nonsense). At midnight, after the fast but before the feast, children place their shoes by the fire in anticipation of presents, while the adults set up the family’s creche de noel, Christmas crib, a treasured collection of clay figurines, some of them very old indeed, kept from year to year.

While most of the accompaning clay figurines, santons, hand-painted by the maitre santonnier rather than plastic, are traditional: singing angels, shepherds with their sheep, cattle munching hay, others are local tradesfolk - farmwife with chickens, fisherman with fish, baker with bread, forester with firewood. And, as with real life, all is not sweetness and light: there’s little red devil with horns tucked somewhere among the holy visitors, and the caga-blea, a red-faced vagrant with trousers round his ankles, crouching in a ditch. Eagerly awaited, too, is the yearly payback in miniature - corrupt government minister, greedy banker, cheating wine-seller, lying bureaucrat - to delight those in the know.

Feast follows fast, as in Vaison. Roast birds (partridge, pheasant, guineafowl rather than turkey) and perhaps an apple-and-walnut double-crust pie, croustade, made with a filo-like pastry stretched between the fists. Next day, with the party all done and dusted, early-rising children are expected to leave their parents to sleep off the effects in peace and pay a visit to grandparents and elderly relatives, some of whom might tuck a note in someone’s pocket. To cure a Provençale hangover, a strong infusion of sage and garlic generously laced with olive oil will do the trick. Drink it up with a chunk of fougasse, while it’s still hot.

p.s. next week: more Christmas food - what else?.

p.p.s. beloved paid subscribers will shortly be in receipt of instructions for the fougasse (as above, with gratons, little scraps of crisp pork-skin) and a fabulous buche de noel with chestnut icing. Maybe.

How very charming. In the Philippines, we have the noche buena on Christmas Eve…usually, lechon, relleno, embotido, queso de bola, hamon, leche flan…from the Spaniards…after all we were a colony for 300 years and the ubiquitous noodles called pancit bijon from the Chinese!

A glorious post. Truly so delicious to read Reminds me of that post New Year adventure in Uzés. And the reeds bending in the stiff Camargue breeze. Wish we had had the luck then to eat as well as you describe.