Sicilians just love it, Calabrians couldn’t live without it, chili does glorious things for practically anything half-way edible, as the Old World learned from the New post-1492. Which was the year that Moorish Al-Andaluz fell to the Fernando of Aragon and Isabel of Castile and closed the gates to the spice-routes of the East. Which convinced the Catholic queen to empty the royal treasure chest to provide a fast-talking adventurer from Genoa with the wherewith to search for the spice-islands from the west.

Replicas of the crazy Italian’s galleons - the Pinta, Niña, and Santa Maria - were available for inspection by the general public, me, at the quayside during Seville’s Expo '92, alongside a replica of Magellan’s flagship, La Victoria. Nailed to a beam in the hold, was a list of quartermaster's stores sufficient to feed 243 men for 2 years that included 181,000 litres red wine, 7,700k chickpeas, 2,300k fava beans, 700k lentils, 7,000 litres olive oil, 2,600 k fatback bacon, 450 dozen sides of salt-cod and 250 strings of garlic.

Chilis, it stands to reason, were not included in the pre-columbian store-cupboard. However, as soon as word got around of a fruiting plant that was as palate-pleasing as pepper (which was imported, expensive, unavailable to the poor), spread like wildfire. Mind-altering botanicals probably helped. Chilis are addictive (they've done the chemistry). The active ingredient, capsaicin, floods the brain with endorphins as produced by racing drivers and fighter-pilots in response to danger. Which is why babies, given a taste of chili, spits it out. Grownups, on the other hand, have to learn to tolerate it before they can learn to love it. Which is probably why we do it.

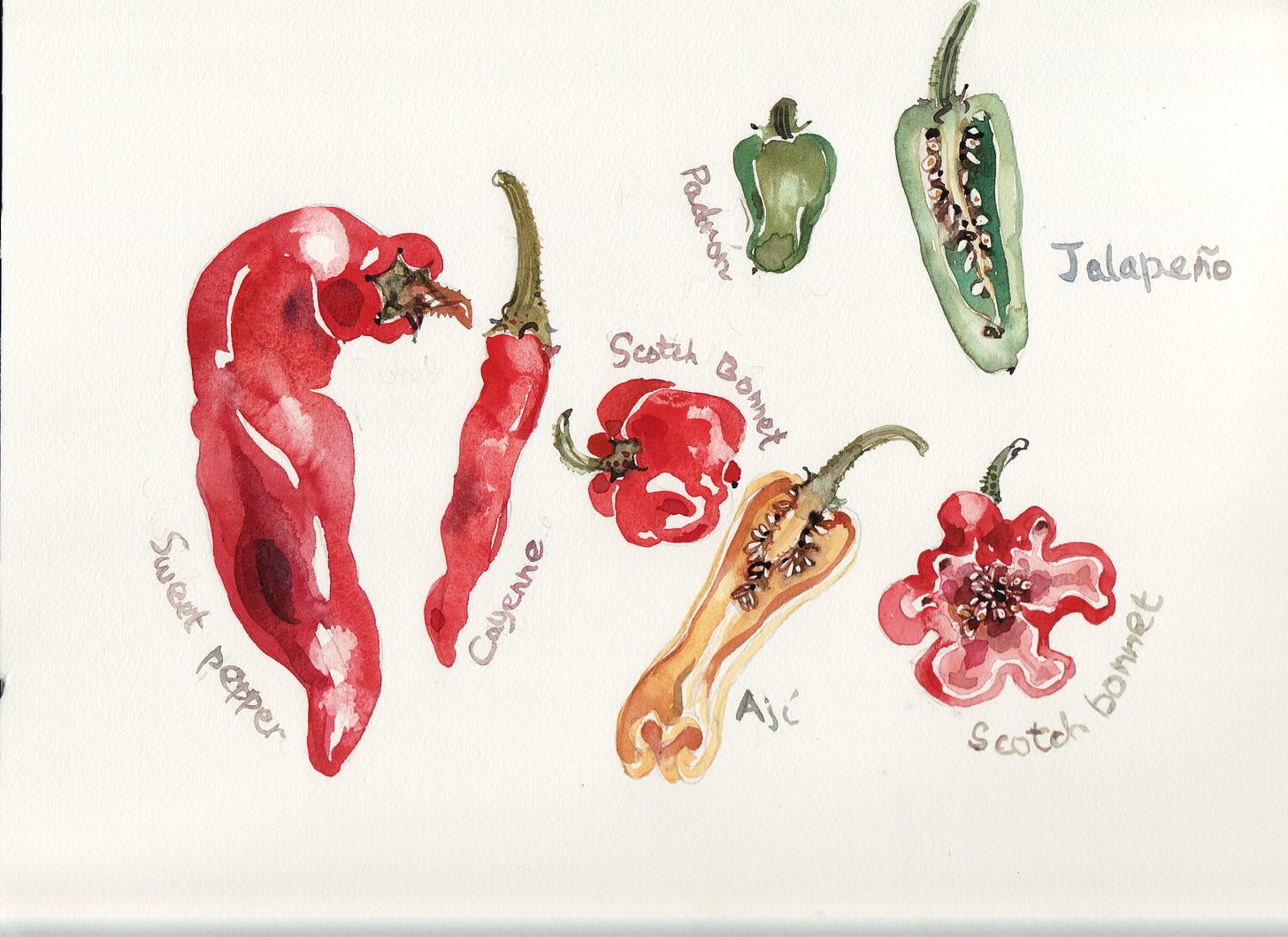

C. annuum and C. frutescens are, it is or was agreed (there are other candidates, five or twenty-five, depending on who’s talking) the mother and father of the family capsicum. All are fiery in land of origin. Mildness and sweetness such as is found in salad-peppers, is the result of selective breeding. C. annuum is (mostly) responsible for the thick-fleshed, salad-pepper line of descent that comes from the Mexican breed, while C. frutescens, an Andean native with branches in the Caribbean, is to blame (mostly) for the thin-fleshed, slender, birds-eye varieties popular throughout India, China and South East Asia.

Right. I'm glad we've sorted that out. Or maybe not, since the original capsicums (the jury’s still out on how many) were already all mixed up botanically by the Incas, Aztec, Mayas and so forth well before the Pinta, Niña and Santa Maria made landfall in the New World.

As a general rule, the little pointy varieties are best for drying at home because they're thin-fleshed and dehydrate naturally if left to their own devices. Green chillis are unripe fruits that, if included raw in salsas, have a fresh, grassy flavour without any loss of heat but are inclined to rot before they ripen As for colour, chilis ripen to red or yellow or orange or brown or deep purple or almost black, depending on the species and who’s been messing around with the genes in the lab.

To choose chilis for drying, look for perfectly ripe fruits with a firm, shiny skin: if wrinkled, they’re past their prime. Check there are no little black patches, particularly round the stem. Unripe green chillies are unsuitable as they’re likely to wither and turn black before they ripen.

To test a chili for fieriness, cut a tiny sliver off the pointy end and touch it your tongue. ‘Nuff said. The heat is concentrated not in the seeds themselves but in the white, woolly fibres which attach them to the interior ridges of the fruit. To mitigate chili-burn, drink a glass of yoghourt or sweetened diluted vinegar (shrub). Plain water just makes it worse.

Among the fieriest and sweetest of those suitable for storing (they keep their colour and fragrance from one year to the next) are the small, spear-shaped upward-facing chilies popular in Calabria in the preparing of 'ndjua, a soft, spreadable, ferociously-fiery chorizo-lookalike that adds colour and flavour to a rural diet that’s largely vegetarian by necessity rather than choice.

My own supplies from last year - now due for renewal but still hanging from a hook in my London kitchen - were acquired when they arrive in early September in the Saturday market in Amantea, an elegant harbour-town midway along the Calabrian coast. Calabrian chilis - peperoncine - are produce bunches of sunny little scarlet fruits on the end of a cluster of stalks, like minature chandeliers.

‘Nduja - only the brave and foolhardy should try this at home - is composed of soft, fatty belly-pork (and other sausagey bits and pieces) ground to a paste with salt and roughly an equal volume of Calabrian chilis (mild as well as hot), stuffed into cleaned-out intestines and hung (in the old days) in the cold dry wind of the mountains of Calabria to mature and ferment much as serrano hams are cured in the mountains of Andalucia. The hams, it goes without saying, went to the landlord to pay the rent. ‘Twas ever thus.

p.s. Beloved paid-subscribers will shortly be in receipt of good things to do with ‘nudja, along with the full list of Magellan’s bill of lading as pinned up in the galley of La Victoria. Fascinating stuff.

p.p.s. more about my travels-with-recipes in Squirrel Pie and Other Stories (Bloomsbury).

Wonderful as always! Thank you Elisabeth!

I recently saw a replica of one of the ships and could not believe how small it was, in fact did not believe it could have been an exact copy! But after looking it up I saw it was pretty accurate!

So apart from the crew they also carried all that food, how amazing that 3 little ships like that went all that way, and back!

I enjoyed this a lot!